A Misanthropy Triggering Argument

The book The Environmental Impact of Overpopulation by Trevor Hedberg, examines the link between population growth and environmental impact, and explores the implications of this connection for the ethics of procreation.

Since I have already reviewed the book Toward a Small Family Ethic – How Overpopulation and Climate Change Are Affecting the Morality of Procreation, by Travis N. Rieder, which raises very similar claims and reaches very similar conclusions (many nearly identical), regarding the implication of the climate crisis for the ethics of procreation, I will not review this book from that perspective as well.

Instead, since one prominent difference between the books is that in Toward a Small Family Ethic antinatalism is barely discussed, and in The Environmental Impact of Overpopulation there is a whole chapter dedicated to antinatalism, and since in this chapter there is an attempt to refute what I find as the most important antinatalist argument – The Harm To Others, I’ll focus on that.

To his credit, as opposed to many other critics of antinatalism, Hedberg doesn’t make do with trying to refute Benatar’s asymmetry argument and his quality-of-life argument, but also tries to refute some of the other main antinatalist arguments such as Benatar’s misanthropic argument, Shiffrin’s consent-based argument, Jimmy Licon’s consent-based argument, Häyry’s Risk aversion argument, and Daniel Friedrich’s duty to adopt.

The reason for my focus on The Harm to Others Argument in this review (here specifically through Hedberg’s critic of Benatar’s misanthropic argument), is not only due to the importance of this topic in my view, but also because I have already indirectly addressed Hedberg’s counterarguments for the other antinatalist arguments that he mentions in this chapter, in the texts about Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument, Benatar’s Quality of Life Argument, The Consent Argument, The Risk Argument, Antinatalism as Fairness, and The Adoption Argument, and sporadically, on many other texts as well.

The Misanthropic Argument

Hedberg presents Benatar’s formula for The Misanthropic Argument as framed in the book Debating Procreation which goes as follow:

-

- We have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing into existence new members of species that cause (and will likely continue to cause) vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death.

- Humans cause vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death.

- Therefore, we have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing new humans into existence.

Before getting into Hedberg’s criticism of Benatar’s misanthropic argument, I want to make a short critical comment on the argument’s name. As mentioned in the review of Debating Procreation, I was very pleased to see that Benatar included The Harm to Others as part of his antinatalism arguments. However, I wish he didn’t title this argument The Misanthropic Argument, because by that, in a way, he continues the anthropocentric tradition of focusing on the human race. Surely, his argument is very unflattering for humanity, but it still focuses on humanity, instead of on its victims, who are supposed to be, at least in The Harm to Others Argument, the center of attention. Benatar calls his other arguments the philanthropic arguments since they focus on humans as victims of procreation, and he calls The Harm to Others Argument – The Misanthropic Argument since it focuses on how destructive and harmful the human race is and so it better not exist. So basically, all his arguments focus on humanity.

Back to Hedberg’s criticism.

Hedberg argues that Benatar’s second premise is obviously true “Even the most optimistic person must acknowledge that human beings often commit moral atrocities, and our history of violence, oppression, exploitation, and deception provides plenty of evidence for the claim” (p. 167), however, since he thinks that the soundness of the argument hinges entirely on the first premise, which according to him is wrong, the whole misanthropic argument is wrong.

And here is why Hedberg argues that the first premise is wrong:

“Benatar thinks that this premise would be widely accepted if the species under consideration were not human. He asks us to imagine people breeding a destructive species of nonhuman animal or scientists releasing a deadly virus and argues that both of these practices would be widely condemned (Benatar 2015, pp. 101–102). Since we hesitate to reach the same verdict about human beings, he suggests our resistance is only due to a bias in favor of our own species. But Benatar makes two mistakes here. First, he is wrong about our judgments about other species. Many predator species cause a great amount of suffering to other animals: they have to savagely kill other animals for their own sustenance. Yet there is not a widespread condemnation of these species or a strong public outcry for the elimination of predation. In fact, we sometimes undertake efforts to re-introduce predator species into environments where their numbers have dwindled. Predators do not cause as much harm as human beings – in large part because their numbers are so much smaller – but these observations provide some evidence that not everyone would immediately accept Benatar’s judgment about the first premise even when it concerns nonhuman species.” (p.115)

First of all, the reason we have, or more accurately should have, a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing into existence new members of a species that causes (and will likely continue to cause) vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death, is very simple, and that is that causing vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death is wrong. And not only that Hedberg knows that, these are the first three premises of the central argument he himself is making in this book, an argument he calls the Population Reduction Argument, and these three premises go as follows:

- We morally ought to avoid causing massive and unnecessary harm to presently existing people.

- Our moral duties of non-harm are just as stringent toward future people as they are toward present people.

- Thus, we morally ought to avoid causing massive unnecessary harm to future people. (p.33)

In his formula he writes about people, however it would be speciesist to suggest that we shouldn’t harm people but we can harm sentient creatures from other species. So if we apply a non-speciesist version of these three premises made by Hedberg to the formula for The Misanthropic Argument which he criticizes, we get a formula that Hedberg (and of course everyone else as well) should agree with. The integrated formula would go something like this:

1) we morally ought to avoid causing massive and unnecessary harm to presently and future existing sentient creatures

2) humans cause vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death to sentient creatures, humans and non-humans

3) Thus, we morally ought to desist from bringing new humans into existence.

Even if Hedberg is right that Benatar is wrong arguing that these practices would be widely condemned, Benatar is right that they should be, and that is the important point to address here.

I don’t think Benatar’s main point in his Misanthropic Argument is one from consistency. The purpose of Benatar’s examples is only rhetoric, not the core of the argument. So there is no need to pick on them while barely addressing the core of the argument which is that we have a duty not to create more members of a species that causes vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death. This is where Hedberg’s focus should be, but it isn’t. Probably because he finds this claim much harder to refute, certainly considering that he himself makes a very similar claim in his own main argument of Population Reduction Argument.

Secondly, although Hedberg is right that members of many predator species cause a great amount of suffering to other animals and that they have to savagely kill other animals for their own sustenance, as opposed to humans, members of predator species don’t have other choices but to bring into existence new members of their species, while humans can choose otherwise. And this is relevant to Hedberg’s claim because in Benatar’s example, although the breeding is of a destructive species of nonhuman animal, it is still humans who are breeding them. It is humans’ decision which should be condemned, not the members of predator species who don’t have other choices but to savagely kill other animals for their own sustenance, and are not moral agents. We can’t convince a destructive species of nonhuman animal not to breed, but we may, and we surely should try to convince humans not to breed a destructive species, even if it is their own.

Thirdly, Hedberg is right that not everyone would immediately accept Benatar’s judgment about the first premise even when it concerns nonhuman species, but that doesn’t make the premise wrong and in fact, in a way it makes it even more right, because human’s poor judgment and their indifference regarding the suffering of sentient creatures caused by other species, only goes to show how cruel, or at least apathetic to others’ suffering they are.

Ironically, according to Hedberg, humans’ apathy to the suffering of wild animals somehow exempts them from their duty to desist from bringing into existence new members of their own extremely harmful species.

Fourthly, Hedberg is factually right that people sometimes undertake efforts to re-introduce predator species into environments where their numbers have dwindled, but that doesn’t make it ethically right. Most people have a very wrong and distorted perception of nature and of life in nature. On the other hand, many antinatalists – the people Hedberg is trying to convince otherwise here – are also EFILists, myself included, and we highly oppose these kinds of efforts. And that is not only when it comes to predator species, but in the case of any species.

The reason for me being an EFIList is the same as my main reason for being an antinatalist and that is since it is impossible for living beings not to harm others. Everyone’s existence is inevitably at the expense of someone else. No one can live without somehow harming others. Whether it is by competing with others for food, water, shelter, mating, the best sunbathing niches, the most shaded spots and etc., or by the more explicit and raw manifestation of living at the expense of others – devouring others.

I am an EFIList because life imposes suffering on trillions upon trillions of creatures just for being alive. When horrendous suffering is simply a natural and inevitable part of life, all the more so when it is so extremely abundant, life is simply, naturally and inevitably horrendous.

So EFILists consider nature as a whole as a giant hell that we wish never exited and would soon stop existing. The fact that some people undertake efforts to further populate this hell, doesn’t make it a cooler hell but actually even hotter one.

For him to refute the first premise of the argument he needs not to prove that people sometimes act in ways that don’t accord with a duty to desist from bringing into existence new members of species that cause vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death, but that we shouldn’t have such a duty. Otherwise how is it not some kind of a case of appeal to popularity? We know people don’t feel like they have such a duty when it comes to other species, and that’s exactly the problem. The point is whether they should have such a duty, and arguing that many act as if they don’t, doesn’t refute the argument itself, but if anything, it indicates people’s inability to apply valid ethical duties (which as earlier mentioned Hedberg himself shares), and being unable to apply valid ethical duties surely doesn’t refute a misanthropic argument…

Fifthly, Hedberg’s claim that predators do not cause as much harm as human beings – in large part because their numbers are so much smaller, seems like ignorance regarding the harms humans are causing.

As oppose to predators who, as he argues, savagely kill other animals for their own sustenance, humans don’t suffice with savagely killing other animals, but condemn each of their victims to a lifetime of torture.

There is no doubt that animals endure extreme suffering when being savagely killed by predators. However, at least these animals are not caged for their entire lives, at least they can move, at least they live in an environment which is natural for them and not a totally alienated, filthy and contaminated one, at least they live in their natural society, at least they have some control over what, and often when, they eat and drink and are not totally controlled by humans’ decisions, at least they can sleep whenever they want wherever they want and not when and where humans decide they would sleep, at least they can spread their limbs, stretch their necks, socialize, breath clean air, clean themselves, fly, roam, run, jump and play. Humans have carelessly taken all that away from the animals they systematically exploit.

And it is not just the external living conditions which are so horrific that they are causing all the animals who are systematically exploited by humans to extremely suffer in every single moment of their lives. The selective breeding that humans have been and still are forcing species of industrially exploited animals to go through is so extreme that many of these animals are suffering just by being alive. Industrial chickens (broilers), hens, pigs, milking cows, salmons and many other farmed fish species, turkeys, sheep, and rabbits have all been designed by genetic selection and other factors so that their profitable body parts (or functions in the case of milking cows, and laying hens) would be as productive as possible, always at the expense of the rest of their body systems. They have become creatures that can’t survive in nature (even if no one would attack them).

As opposed to victims of predators, the lives of humans’ victims are ones in which everything hurts all the time, lives where there is not even one moment without pain, stress, crowding, boredom and filth. Most animals in factory farms don’t even know how it feels not to be in pain.

And humans are also causing immeasurable suffering to many animals in nature, for example by spilling toxic wastes into their habitats, by physically destroying their habitats, by filling their habitats with plastic, aluminum, oil and etc, by causing noise pollution, light pollution, air pollution and other kinds of pollution, and by emitting CO2 and so changing their planet’s climate. No members of any predator species are doing any of that.

And an even acuter case of ignorance is coming from what Hedberg refers to as Benatar’s second mistake:

Hedberg’s Second Mistake

Hedberg argues that:

“The second mistake is that Benatar overlooks the fact that human beings also perform actions that are morally good. No one is morally perfect, but few are as monstrous as the murderers and animal abusers that he cites as examples of human evil. Surely the good that people do counts in favor of creating more of them, so we need further discussion of just how great the harms of the typical person are and how they compare to the good that the person does.” (p.116)

Once again Hedberg displays supposedly blunt ignorance regarding the harms humans are causing (though as you’ll see further in the text this is not a case of ignorance). Unfortunately, the truth is that only few humans are not murderers and animal abusers.

It is very hard to accurately assess the harms caused by each person since it depends on various factors such as location, socioeconomic status, consumption habits, life expectancy, livelihood, diet and etc., however, regardless of any circumstances, harming numerous others is inevitable. And the most immediate and prominent harm is caused by what people eat.

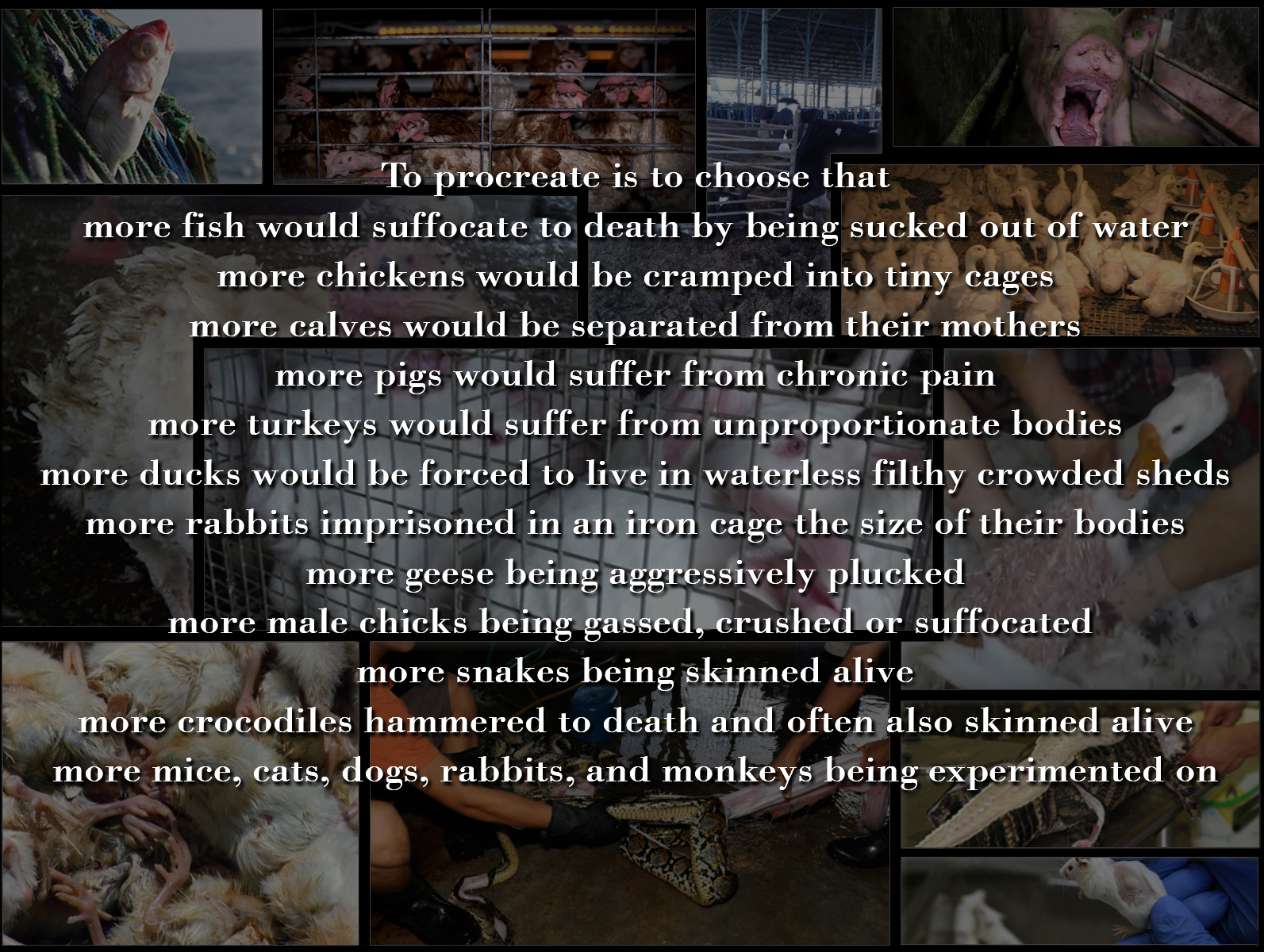

Every person has to eat, and every food has a price. Unfortunately, most people are choosing the ones with the highest price – animal based foods. Therefore in most cases procreating is choosing that more fish would suffocate to death by being violently sucked out of water, that more chickens would be cramped into tiny cages with each forced to live in a space the size of an A4 paper, that more calves would be separated from their mothers, and more cow mothers would be left traumatized by the abduction of their babies, it is choosing more pigs who suffer from chronic pain, more lame sheep, more beaten goats, more turkeys who can barely stand as a result of their unproportionate bodies, more ducks who are forced to live out of water and in filthy crowded sheds, more rabbits imprisoned in an iron cage the size of their bodies, more geese being aggressively plucked, more male chicks being gassed, crushed or suffocated since they are unexploitable for eggs nor meat, more snakes being skinned alive, and more crocodiles and alligators being hammered to death and often also skinned alive to be worn, and more mice, cats, dogs, fish, rabbits, and monkeys being experimented on.

Each person directly consumes thousands of animals. More accurate average figures are varied according to each person location. An average American meat eater for example consumes more than 2,020 chickens, about 1,700 fish, more than 70 turkeys, more than 30 pigs and sheep, about 11 cows, and tens of thousands of aquatic animals, some directly and some indirectly (as many of which are fed to consumed animals).

Since most humans, more than 95% of them actually, are not even vegans – the most basic and primal ethical decision one must make – procreation is practically letting a mass murderer on the loose.

Factory farming is the worst and cruelest way people feed themselves. But it is not that other options are harmless. It is impossible to eat without harming someone, somewhere along the line. And it takes a very long line to make food, any food. Much longer, and much more harmful than people tend to think. For more details about the harms involved with plant based agriculture, as well as numerous other harms that each human is bound to cause simply by living in this world, please read The Harm to Others.

The basic idea that it is important to comprehend is that living on a planet with limited resources, no one can really avoid getting in conflict with others. Every action people make affects others, so it is even theoretically impossible to fulfil the most basic ethical requirement – do no harm. And practically, it is far from being the case that people are harming only since and when they cannot do otherwise. I wish people were harming others only for survival reasons. Reality is unfortunately much crueler. People harm, exploit, torture, humiliate, deprive, attack, ignore, abuse and whatnot, for much less essential reasons. Other animals mostly don’t harm others if it is not necessary for their survival, but this is far from being the case when it comes to humans who very often harm out of selfish reasons. They don’t harm others because they have things that they need, but mostly because they have things that they want.

In addition to animals harmed by people who directly consume them, and to animals harmed by people who pollute their air, land, food and water, steal their water, destroy their habitats, alter the climate, throw their waste into their homes, bombard their homes with noise and light, and etc. other humans are also victims of people’s want of things.

As opposed to what most people want to believe, there are still slaves around the world and it is actually quite a common phenomenon, not to mention workers’ exploitation which is so abundant that there is no country in the world where it doesn’t exist. Most people don’t consider workers’ exploitation that is common in mines, the construction industry, the agriculture industry, and of course in sweatshops, as slavery, but I fail to spot the fundamental difference. When people can theoretically leave their horrible job but practically can’t, when people work very hard for very long hours with very few breaks if any, when they can’t fight for their rights or even negotiate some of their working conditions, when they must jeopardize their physical and emotional health, when the pay is barely enough for them to survive, even if formally it is not slavery, practically it is.

Modern slavery is everywhere. Practically it is impossible for people to avoid supporting it, and most don’t want to. They enjoy a high level of living largely because of this modern slavery. They can buy cheap commodities such as chocolate, coffee, clothes, salt, sugar, rice, wheat, mobile phones, shoes, toys, and etc. thanks to the misery of others.

Modern slavery is mostly a product of structured poverty, and as long as poverty exists, slavery would exist too. It is not very likely that people would end poverty and slavery any time soon, and so slavery is probably here to stay. Every human supports slavery in one way or another. Some do it sorrowfully and unintentionally, and most do it indifferently. But everyone, somehow, encourages this gruesome human feature which is very ancient, and shows no signs of decline. Therefore every creation of a new person is also a creation of a modern salve or a modern enslaver.

So there is no need for no “further discussion of just how great the harms of the typical person are and how they compare to the good that the person does”, as this very partial list of harms each human is causing, not to mention that a full list would be practically endless, absolutely dwarfs any list of actions that according to Hedberg are good.

And one last quick point. I think that the fact that no one is morally perfect as Hedberg argues, shouldn’t be taken for granted. If we take the duty (that he himself claims for) that we morally ought to avoid causing massive and unnecessary harm, seriously, the fact that we can’t, is in my view, sufficient to constitute a duty not to procreate. If humans can’t avoid harming others, let alone to such a destructive extent, how can they justify creating more of themselves?

But even sadder than the fact that no one is, or can be, morally perfect, is that practically speaking, most people, even if some of them don’t mean to, are not only far from being morally prefect, but are bound to be morally evil.

The Frustrating Argument

What makes things even more frustrating about this book, is that it has a whole chapter devoted to the issue of nonhuman animals. Conveniently, Hedberg chose to place this chapter second to last, right before his concluding remarks, and further away from where it should have been discussed, in The Misanthropic Argument for antinatalism. Hedberg probably knows that seriously considering the harm humans are causing to other animals would make it impossible for him to suggest a serious refute to the misanthropic argument, so he considers the harm humans are causing to other animals, separately, all the more so under a section he calls Lingering Questions (instead of Extremely Urgent Questions for example), a move that in his view enables him to reach, what I view as, utterly not serious enough conclusions.

Since the gap between Hedberg’s claims along this chapter and his practical conclusion in the book in general is so huge and speaks for itself, I allowed myself to add some long quotes from the book:

“Unfortunately, many of our ways of treating animals still reflect an extraordinary bias in favor of our own species. Some are tempted by the thought that human beings are unique in some way that justifies according them a higher moral status than all other animals, including conscious ones. As mentioned earlier, the phenomenon of severe cognitive impairment raises major challenges for this view, but even human beings generally do have a higher moral status than nonhuman animals, it does not follow that animals have no moral status or that the difference between humans and animals is so great that we are justified in ignoring animals’ interests. To revisit an important point from Chapter 3, one of the most basic moral imperatives is the duty to avoid causing unnecessary harm to someone else. Conscious animals, since they can experience pain and have their interests stifled, can be harmed. Thus, at a bare minimum, our treatment of conscious animals should not cause them unnecessary harm.” (p.153)

“Even using only the basic moral imperative not to harm animals unnecessarily, we can identify a staggering amount of wrongdoing that is taking place. Every year, more than 70 billion land animals are slaughtered for human consumption (UN Food and Agricultural Organization 2019). This is almost ten times the total number of human beings who inhabit the Earth, and this level of killing takes place every year. Most of these animals are raised in industrial settings, often called “factory farms,” where they suffer severely before being slaughtered. The objective in factory farms is to produce as much meat as efficiently as possible. The motivation for this approach is entirely economic: having more animal products to sell leads to higher profits. Since animals are viewed purely as economic resources in these settings, their welfare is not a high priority. The result is that animals suffer greatly so that meat can be cheap and widely available.” (p.153)

“The suffering imposed on factory-farmed animals is severe yet produces only a minor benefit to people – the availability of cheap meat. Can so much suffering and death really be justified by such a meager benefit to humans? Given what we know about animal consciousness and its connection to having interests, the answer is surely no. If we give the welfare of animals any meaningful weight, then treating animals in this manner is morally impermissible. Yet tens of billions of them suffer such a fate every year. And that number does not even include the creatures that are harvested from the ocean. If we were to add them to the tally of animals killed by humans annually, the total number might well surpass one trillion.” (p.154)

“As outlandishly high as the number of animal deaths already is, this figure will almost surely increase in the near future. Research from the UN Food and Agricultural Organization projects that demand for meat will rise 73 percent between 2010 and 2050 (Gerber et al. 2013). This estimate accords with the worldwide trend toward increased meat production. Over 70 billion animals were slaughtered for human consumption in 2017, but less than 50 billion were slaughtered for our consumption in 2000 (FAO 2019).” (p.154)

“Meat demand is rising for two reasons. First, when nations develop, their populations tend to increase their meat consumption. Several highly populated nations, including China and India, are expected to see a huge rise in meat demand as their economic circumstances improve. Second, as human population grows, there are more mouths to feed. Since meat eating is such a common human behavior, more people generally results in more meat consumption. In tandem, these two factors make it inevitable that meat demand will rise significantly as the century progresses.” (p.154)

“Many animal activists advocate a societal shift toward vegetarian or vegan diets, but the global trend is pulling in the opposite direction. A widespread abandonment of meat consumption will not happen anytime soon. Now that does not mean that trying to get people to eat less meat is pointless: raising awareness of the morally unacceptable aspects of current farming practices and advocating for social change are critical aspects of working toward a long term solution. My point is that trillions of animals will suffer and die before that solution materializes. So until we shift to an agricultural system that imposes far less harm on animals, we must consider alternative ways to reduce animal suffering. It is obvious that the size of our population will play a huge role in the overall demand for meat, so one clear strategy for reducing animal suffering is to pursue population reduction.” (p.155)

“All told, our world features an extraordinary amount of animal suffering and death, and much of it is caused directly by human actions. Conscious animals have direct moral standing, and the vast majority of the animal suffering and death that we cause is unnecessary. Population reduction could play a significant role in decreasing the amount of animal suffering and death that occurs in the future. Thus, if we properly acknowledge the moral significance of animal consciousness, we have even stronger moral reasons to adopt policy measures that lower fertility rates than if we focus entirely on human interests and values.” (p.155)

“I have argued throughout other areas of this book that we have a moral duty to pursue population reduction even if we limit our moral concern to the interests and values of human beings. However, there is compelling evidence that some entities other than humans have direct moral standing. The case that conscious animals have such standing is all but irrefutable in light of the empirical evidence about their cognitive capacities. A failure to account for the suffering of conscious animals shows either ignorance or an unjustifiable bias in favor of our own species. How far moral standing extends beyond conscious beings is much less certain, but even if we limit the scope of our moral concern to human beings and conscious animals, the hundreds of billions of animals that are killed each year to provide sustenance for us provide overwhelming evidence that our current practices are unjustifiable. One of the biggest reasons why we produce so much meat and harvest so many fish is to feed our burgeoning population. Reducing our numbers would mean fewer of these animals have to suffer and die. Halting our population growth would be a boon to the welfare of both future people and our nonhuman brethren.” (p.157)

Instead of inferring an explicit and radical version of antinatalism from all these claims, Hedberg makes do with the speciesist suggestion that all the horrors that all the humans are causing to all the animals, as harsh and unequivocal as they are in his own words, are enough only to strengthen his population reduction argument, but for some reason not to support, not to mention, form the Harm to Others Argument for Antinatalism.

And if all that he wrote is not sufficiently convincing to constitute the harm to others argument for antinatalism, it sure is sufficiently convincing for us antinatalists to constitute the misanthropic argument in general.

References:

Hedberg, Trevor. 2017. The Environmental Impact of Overpopulation: The Ethics of Procreation

New York: Routledge

Rieder, Travis. 2016. Toward a Small Family Ethic: How Overpopulation and Climate Change Are Affecting the Morality of Procreation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Leave a Reply