The second chapter of the book contains the heart of Benatar’s theory and by far the most controversial argument he makes. In fact even many antinatalists disagree with the argument he makes in this chapter including myself. I’ll briefly present the argument, some of its main criticisms, and why despite its essential flaw, it is nevertheless always a harm to create new people.

The following is Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument taken from the second chapter of the book called ‘why coming into existence is always a harm’, and to do justice to it, I’ve chosen a relatively long quote:

“We infrequently contemplate the harms that await any new-born child—pain, disappointment, anxiety, grief, and death. For any given child we cannot predict what form these harms will take or how severe they will be, but we can be sure that at least some of them will occur. None of this befalls the non-existent. Only existers suffer harm.

Optimists will be quick to note that I have not told the whole story. Not only bad things but also good things happen only to those who exist. Pleasure, joy, and satisfaction can only be had by existers. Thus, the cheerful will say, we must weigh up the pleasures of life against the evils. As long as the former outweigh the latter, the life is worth living. Coming into being with such a life is, on this view, a benefit.

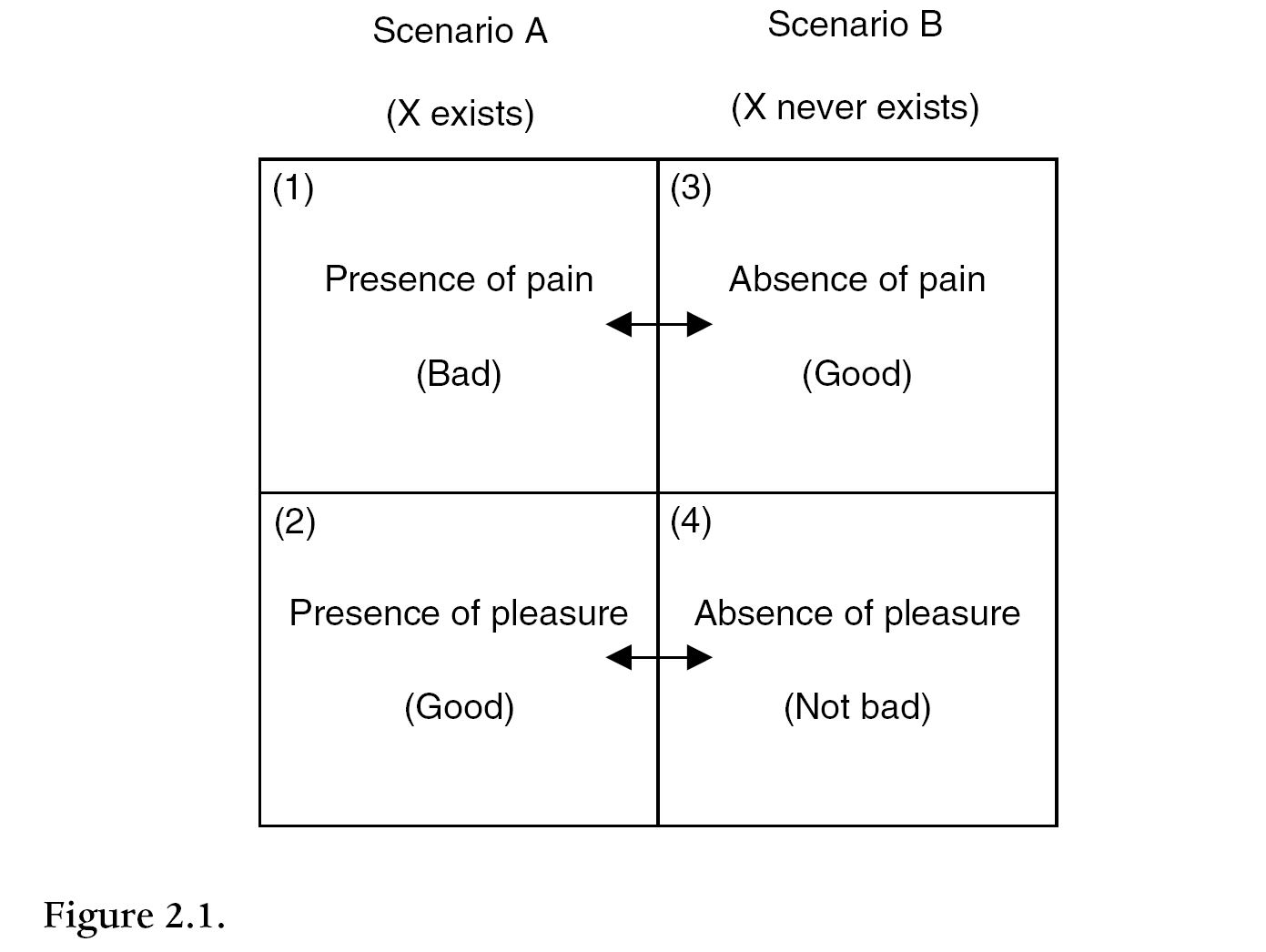

However, this conclusion does not follow. This is because there is a crucial difference between harms (such as pains) and benefits (such as pleasures) which entails that existence has no advantage over, but does have disadvantages relative to, non-existence. Consider pains and pleasures as exemplars of harms and benefits. It is uncontroversial to say that

(1) the presence of pain is bad,

and that

(2) the presence of pleasure is good.

However, such a symmetrical evaluation does not seem to apply to the absence of pain and pleasure, for it strikes me as true that

(3) the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone, whereas

(4) the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence is a deprivation.” (p.29-31)

“Figure 2.1 is intended to show why it is always preferable not to come into existence. It shows that coming into existence has disadvantages relative to never coming into existence whereas the positive features of existing are not advantages over never existing. Scenario B is always better than Scenario A.” (p.48)

That is basically how he concludes that it is always better never to come into existence.

When Benatar argues that the absence of pain of non-existent people is good and that the absence of pleasure of non-existent people is not bad, he is not making an impersonal evaluation (an evaluation that something is good or bad without being good or bad for somebody), rather he is making judgments whether being created is in the interests of the created person or whether it would have been better for that person to have never been. Therefore, one of the most common criticisms of Benatar’s asymmetry argument is that he ascribes interests to non-existent persons. Many people have difficulty making sense of the idea that never existing can be better for a person who never exists, because there is no subject for whom never existing could be a benefit. In other words, they wonder how can the absence of pain be good, if there is no one for whom it would be good? For something to be good, it needs to be good for someone, and in non-existence there is no someone. Only existing beings can be deprived of something. Hypotheticals are abstractions with no feelings nor preferences nor nothing. How can it be in the interest of not-existent not to exist, if only actual beings have interests?

Predicting this objection, Benatar writes in the book:

“Now it might be asked how the absence of pain could be good if that good is not enjoyed by anybody. Absent pain, it might be said, cannot be good for anybody, if nobody exists for whom it can be good.

The judgement made in 3 (the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone) is made with reference to the (potential) interests of a person who either does or does not exist. To this it might be objected that because (3) is part of the scenario under which this person never exists, (3) cannot say anything about an existing person. This objection would be mistaken because (3) can say something about a counterfactual case in which a person who does actually exist never did exist. Of the pain of an existing person, (3) says that the absence of this pain would have been good even if this could only have been achieved by the absence of the person who now suffers it. In other words, judged in terms of the interests of a person who now exists, the absence of the pain would have been good even though this person would then not have existed. Consider next what (3) says of the absent pain of one who never exists—of pain, the absence of which is ensured by not making a potential person actual. Claim (3) says that this absence is good when judged in terms of the interests of the person who would otherwise have existed. We may not know who that person would have been, but we can still say that whoever that person would have been, the avoidance of his or her pains is good when judged in terms of his or her potential interests. If there is any (obviously loose) sense in which the absent pain is good for the person who could have existed but does not exist, this is it. Clearly (3) does not entail the absurd literal claim that there is some actual person for whom the absent pain is good.” (p.30)

And later in an article called Still Better Never to Have Been: A Reply to (More of) My Critics:

“Now it is obviously the case that if somebody never comes into existence there is no actual person who is thereby benefited. However, we can still claim that it is better for a person that he never exist, on condition that we understand that locution as a shorthand for a more complex idea. That more complex idea is this: We are comparing two possible worlds—one in which a person exists and one in which he does not. One way in which we can judge which of these possible worlds is better, is with reference to the interests of the person who exists in one (and only one) of these two possible worlds. Obviously those interests only exist in the possible world in which the person exists, but this does not preclude our making judgments about the value of an alternative possible world, and doing so with reference to the interests of the person in the possible world in which he does exist. Thus, we can claim of somebody who exists that it would have been better for him if he had never existed. If somebody does not exist, we can state of him that had he existed, it would have been better for him if he had never existed. In each case we are claiming something about somebody who exists in one of two alternative possible worlds.

When we claim that we avoid bringing a suffering child into existence for that child’s sake, we do not literally mean that nonexistent people have a sake. Instead, it is shorthand for stating that when we compare two possible worlds and we judge the matter in terms of the interests of the person who exists in one but not the other of these worlds, we judge the world in which he does not exist to be better.” (p.125-126)

I agree obviously with the common objection that the non-existent can’t be benefited. However, this is not the main problem with Benatar’s asymmetry. The main problem is not that a person exists in one world but not the other, and not even that the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone, but that in the same world, the one in which the person doesn’t exist, when it comes to the absence of pain the person is treated as if s/he exists (otherwise the absence of pain can’t be good for him/her) but when it comes to the absence of pleasures s/he is treated as if s/he doesn’t exist (otherwise the absence of pleasures would be bad for him/her, and the only reason it isn’t is because the non-existent is not deprived of pleasures). In other words, the claim that the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone, is a counterfactual claim (statement which expresses what could or would happen under different circumstances). Meaning, if that person were to exist pain would be bad for that person. However, he doesn’t use the same standard when it comes to the absence of pleasures. If pain would be bad if someone would exist in quadrant 3 in figure 2.1 than how come pleasure wouldn’t be good if that person would exist in quadrant 4? Just as pain would be bad for person X if existed, so would pleasure be good if person X existed. Just as the non-existents are not in a position to miss any pleasure, they are also not in a position to be relieved from not experiencing any pain. Since his argument is counterfactual, the absence of pleasure should be valued as bad for the non-existent, just as the absence of pain is valued as good for the non-existent.

So even if we accept his explanation regarding ascribing interests (or at least counterfactual preferences) to the non-existent, I still can’t figure how he can use one standard for quadrant 3 and another for quadrant 4. It can’t go both ways, if pleasure is good then its absence is bad. If one wants to argue that the absence of pleasure is not bad since there is no one to be deprived of them, then the same standard must be applied in the case of the absence of pain, meaning it can’t be good if there is no one to enjoy its avoidance. So the absence of pain can be valued as ‘not good’ and the absence of pleasure can be valued as ‘not bad’, but then the matrix is symmetrical, and obviously the argument loses its point.

If the problem is still not clear enough, here is an explanation by another antinatalist philosopher called Julio Cabrera (whose ideas I am referring here) who disagrees with Benatar’s asymmetry argument:

“If the counterfactual conception of a “possible being” is used in the same way when assessing the absence of pleasure and the absence of pain, the alleged asymmetry would not follow. What is happening here is that in certain moments of his argumentation, Benatar uses a different notion of “possible being”, a concept that could be called “empty”, according to which a “possible being” would be the one that simply is not present in the world and neither is counterfactually represented. Clearly, these two concepts are incompatible: when using the counterfactual conception, it is irrelevant that the being is not present in the world, since he/she is counterfactually represented; and when using the empty conception, it is irrelevant making considerations of any kind about the possible being because, in this conception, there is no such a being at all. Benatar allows the “counterfactual conception” of a possible being when dealing with the absence of pain, but he imposes the “empty conception” when dealing with the absence of pleasure.

Ideally, someone could say (using the empty conception) that for the absence of pain to be good, there has to be someone for whom this absence is enjoyable, and (using the counterfactual notion) that the absence of pleasure is bad even when there is nobody to suffer from it. If the “possible being” is conceived in (3) in the empty conception, the absence of pain would not be good (or bad), and if the “possible being” is conceived in (4) in the counterfactual conception, the absence of pleasure would not be not bad, but bad. This would be establishing the asymmetry of the way around of Benatar, and with the same drawbacks. In fact, to stay within the logical requirements, it would be right using both for the absence of pleasure and the absence of pain, the same conception of “possible being” whatever it is (counterfactual or empty). What is illegitimate is to mix them within the same line of reasoning.” (Cabrera 2014, p.219-220)

One way to show that the main problem with Benatar’s asymmetry argument is not that it attributes interests to non-existent, but that it ascribes two different categories to the two quadrants (quadrant 3 and 4) which are on the same column (and so should have been treated the same in a categorical sense), is to rephrase it so it would ascribe the same category to the two quadrants. Then the conclusion would be something like: The non-existent doesn’t benefit from the absence of pain since there is no one for whom it would be a benefit, but the non-existent also doesn’t lose from not existing since the non-existent is not deprived of any pleasure.

But even with this formulation of the argument, anyone who thinks that pleasures are good can reply that even if missing pleasure is not bad since no one is deprived of them, creating someone who would experience pleasures is good, given that pleasures are good by themselves.

Many pro-natalists can argue that their claim isn’t that they are harming someone by not bringing them into life of pleasures, but that they are benefiting someone in doing so. They may claim that they are not motivated to procreate since otherwise they are wronging someone who could have enjoyed pleasures, but that they are bestowing someone the opportunity to experience pleasures. This argument is not addressed by Benatar’s asymmetry argument.

Of course, there are many other arguments against this pro-natalist claim, such as that there is no way to guarantee that someone enjoys one’s life, that there is no way to avoid suffering, that there is no way to guarantee that the pleasures would outweigh the suffering, that there is no way to obtain consent, that while it is morally justifiable to cause someone suffering without their consent if it is impossible to get one in order to reduce the suffering of that person, it is morally wrong to cause someone suffering merely to benefit that person, and of course, that not only that there is no way to guarantee that the created person won’t experience suffering, it is absolutely guaranteed that that person would cause suffering to others. So even if it was true that people are creating new people because they want to benefit them, while doing so they are making the lives of existing sentient beings even worse than they already are, and therefore procreation is never morally justified.

I wrote ‘even if it was true that people are creating new people because they want to benefit them’ because it is never the reason, and that is also important and relevant to mention. If increasing pleasures was really the motivation behind people’s decisions, then they can increase the pleasures of existing people. They can benefit people to whom it was already decided without their consent that they would exist and therefore suffer and die. If people want to benefit others so much, they can do so with ones who can give their consent, and that their inevitable suffering was already chosen for them by their parents. Why not focusing on existing people who already exist and suffer? Why create new people who might benefit but would most certainly be harmed, instead of benefiting existing people without harming them on the way? The answer is that obviously it is just an excuse. Nobody is procreating to benefit anyone. You can’t benefit someone who doesn’t exist, and someone who doesn’t exist is not harmed by not existing so need not to be saved. Non-existents are not trapped in glass containers outside of existence pleading that someone would bring them in. There is nobody in non-existence, so there is no one who needs to experience anything. There is nobody who needs to be created so it can be bestowed with benefits or to balance good and bad. People don’t procreate to benefit others, but to benefit themselves.

However, although there are anyway other more sound and convincing arguments for antinatalism (such as the ones mentioned above), the asymmetrical argument does work, but in a different formulation than Benatar’s.

Besides the mentioned problems with his version, like some other antinatalists, I think that pleasures are not really intrinsically good but addictive falsehood smoke screen illusions, which trap sentient beings to an endless, pointless and vain seek for more of them. Pleasures are in the best case instrumentally good which mostly ease some of the pains of life, but far from all of them. Pleasures are not intrinsic, and that is since basically they stem from wants. Pleasures are preceded by wants which are the absence of objects desired by subjects. People want because they are missing something. They seek pleasures to release the tension of craving. Craving or wants, are at least bad experiences if not a sort of pain. Pleasures are short and temporary, and compel a preceding deprivation, a want or a need, which is not always being fulfilled, rarely to the desired measure, and almost never exactly when wanted. And even when desires are fulfilled, the cycle starts again. Maybe some would find pain as not the most accurate term for this case, but frustration definitely fits.

Bad experiences almost always precede pleasures, but it is even worse, pains are the natural default state. If one would stop all action, pains would attack very shortly in the form of hunger, thirst, boredom, loneliness, physical discomfort, thermal discomfort and etc. Pain comes if one does nothing, it is the default state. Pleasures don’t come if we do nothing, they usually require effort, and usually only for a brief positive experience.

Pain is a very vicious tyrant, it forces us to react. Some of the reactions are found satisfying and therefore we mistakenly call them pleasures, but it is only a manipulative system which requires a preceding deprivation, and compels a following deprivation of the next “pleasure”.

That doesn’t mean, if to take the common and intuitive example of food, that the pleasures from food stem from the pains of hunger. Some do argue that, but since quite often people take pleasure in food when they are not hungry, and in many cases their pleasure from it is experienced as a stronger feeling than the pains of hunger (usually the case in the rich world), this is not how I think this argument should be based. It is inaccurate to balance the feeling of hunger before a meal and the feeling of pleasure during it, but all the pains, and all the hard work preceding the pleasure, with the consequent gains. And in relation to food, the balance should be between all the efforts and frustration put in so food can even be available for someone, with the pleasure it provides. Then, it is hardly likely that it was worth it. Not only the pains of huger should be compared with the pleasures from food but also all the labor of providing it.

And that’s only a more accurate balancing between the negative and positive within the same person. The case of food particularly is the last example that can be referred to as a balance between a person’s hunger and pleasure from food. Food is by far the biggest source of suffering in the history of this planet. Therefore the pleasure from food must be balanced with all the suffering caused to produce it. The case of food is totally distorted without considering all the involved exploitation, pollution, demolition, plunder, murder, and enslavement. All the exhausting labor of all the people along the production chain of food in our globalized capitalistic world, must be considered, and obviously, and without any comparison, all the animals’ suffering. All the pleasures from all the food in one’s life can never be balanced with even one second in any factory farm.

Another common example pro-natalists give is sexual pleasure. In this case, same as in the case of food, I disagree that the pleasure from sex is merely the relief from the pains of sexual desire. I think that like in the case of food, it is wrong to compare the pleasure from sex with pains of sexual desire prior to the sexual act, but if anything, to compare all the pleasures from all the sexual acts with all the frustrations of all the sexual desires. Comparing specific anecdotes would give the wrong impression that the pains of sexual desire are equivalent to the pleasure from sex which I think is not the case, and also that every moment of sexual desire ends up with sexual pleasure which is far from being the case. A much more over-all balancing between sexual satisfaction and dissatisfaction is required to determine whether sex can be considered as pleasurable, and even that would be only partial. We must also consider all the efforts put in by people so sex can even be an option. This is not the place to dig into that but I suppose it is obvious to you that people and other animals invest immense amounts of time and energy just to be in the position that sex would even be an option. All these efforts must also be considered before sex is labeled as pure pleasure.

And of course, again, like in the case of food, the harms to others must be considered as well (if not primarily). Not only the harms by the production and waste of the many peripheral devices involved in sex, nor the potentially greatest harm of sex (when unsafe) which is that another person might be born, but what it makes people do to each other.

Sex is mentioned as one of the various examples proving that bad experiences have a much stronger effect than good experiences, in the article Bad Is Stronger Than Good, which I address here. Here is part of the explanation:

“Sexuality offers a sphere in which relevant comparisons can perhaps be made, insofar as good sexual experiences are often regarded as among the best and most intense positive experiences people have. Ample evidence suggests that a single bad experience in the sexual domain can impair sexual functioning and enjoyment and even have deleterious effects on health and well-being for years afterward (see Laumann, Gagon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999; Rynd, 1988; note, however, that these are correlational findings and some interpretive questions remain). There is no indication that any good sexual experience, no matter how good, can produce benefits in which magnitude is comparable to the harm caused by such victimization.” (p.327)

This example is not only a very strong indication that bad is stronger than good but also that sex is far from being a source of pure pleasure. Sex is also an infinite source of pain. It is true that some of it is not merely sexual originated, for example rape is mostly about power and dominance, but not only, and rape is not the only sexually related way people hurt each other. It is probably the worst one on the scale, but there are plenty of other ways, from lies and manipulation to extortion and humiliation. The limits are set by the human imagination. To consider sex as a source of pleasure, like in the case of food, is ignorant if not cruel.

According to the “set point” theory of happiness, which many psychologists find convincing nowadays, mood is homeostatic. That means that even desirable things which people do manage to obtain, are satisfying at first, but eventually people adapt to them and return to their “set points”. Therefore they usually end up more or less on the same level of wellbeing they were before. That’s why some argue that people actually run on hedonic treadmills.

Pleasures are unguaranteed, brief, and at some point become boring and ineffective. There is no chronic pleasure, but there is definitely chronic pain. And it is quite abundant. Pain is always guaranteed.

People pursue pleasures not necessarily due to their great positive power, but due to the great negative power of cravings for them when they are absent. Strong addiction is not necessarily indicative of the pleasure of having, but can definitely be about the great pains of not having.

We are forced to want pleasures, and wants are not good. That is not only because wants are not always being satisfied, but also and mainly because usually, when wants are satisfied, it is at the expense of others. Procreation is immoral not only because it is imposing existence on a creature who is designed by default to feel pain, but also and mainly because it is imposing pain on many others as a result of creating that someone. Not every want is principally at the expense of others, but practically it is safe to say that almost all of them are, definitely in the consumerist society. Materialistic desires are usually at the expense of animals and poorer humans. Animals are paying the price for human pleasures not only by being directly consumed, but also by the interminable production of new goods and the throwing away of old ones into their habitats.

In many cases, people are trying to fulfill non materialistic wants, or to compensate for general frustration with consumption of commodities. And even when they don’t, it is in many cases at the expense of other people. It is rarely the case that two people want exactly the same things all the time. In most cases they don’t. In the least worse case they compromise, in the worst ones pressure, manipulations and intimidation are used. Or that all sides live with frustrations. There is no way to win. Nobody lives as they want. Nobody is happy. Everybody is frustrated to some degree. It usually goes under our radar since we are so used to frustrations, and since people tend to internalize the realistic scope of their desires’ fulfillment. But that doesn’t mean they don’t desire totally different things in life. Things they will never get.

Pleasure is not good that should be balanced with pain, but a perpetual need to satisfy unnecessary desires. It is better not to dig the hole in the first place than exert oneself all lifelong with no chance to ever fill it up, and with no point anyway other than that it would be full.

The hypothetical option of providing solutions can’t serve as a justification for creating the problem.

As convincing as I personally find the claim the pleasures are not good, or at least not intrinsically good but merely instrumentally good (easing bad experiences such as pain, boredom and frustration), I can understand why it’s debatable. However the claim that pain is much more important than pleasure is undoubtedly undebatable.

Benatar asked in one of the interviews he gave, would you take one hour of the best pleasure you can imagine in exchange for 5 minutes of torture? Probably no one would take it. And that’s just one example of a thought experiment aiming to show that people’s intuition is that pain is more important than pleasures. Other thought experiments are designed to demonstrate a similar intuition – that avoiding causing someone pain is more important ethically than making someone happy. A generic offhand example could be something like, imagine two worlds, one in which people are in a neutral state, and the other in which people are suffering. We have one button which can increase the pleasure of people in the neutral world and one button that can decrease the suffering in the other world. Even if the pleasure button is 10 times stronger than the pain reliever button, most people would probably go for the pain reliever button, and probably all of them would in the case of equally strong buttons. If you find these kind of thought experiments insufficient, or the appeal to intuition itself as insufficient, and you feel you need some harder science, in the next post I elaborate in detail some scientifically based indications of why suffering is much more important than pleasure.

Anyway, even if one objects to the perspective that pleasure is not good, a non-biased observation must anyway lead to the conclusion that missing unnecessary pleasure is much less bad than forcing unnecessary suffering.

Given that pleasure is not at all good but in the best case actually easing pain, or that it is good but much less good than pain is bad, under both of these alternative perceptions of pleasure, there is an asymmetry since the columns of existence are: pain is bad, and pleasure is not good (or at least not as good as pain is bad), and the columns of non-existence are: the absence of pain is not good (because there is no one to enjoy that good), and the absence of pleasure is not bad (because pleasures are not good and even if they were, there is no one to be deprived of them), so we can argue that non-existence is not good and not bad, and that existence is bad. That is since even if good experiences do exist, and even if they are intrinsically good and not merely instrumentally good, bad experiences are much stronger than them. So in any case it is indeed better never to exist.

Once one realizes that suffering is much more important than pleasures, even without being convinced that pleasures are not even good by themselves but are merely temporary pain relievers in the better case, or frustration enhancers in the worst case, then indeed there is an asymmetry. It is a slightly different formulation than Benatar’s, but it’s definitely an asymmetry which should definitely bring everyone to the rational conclusion that creating someone is always a harm. But do you think people would find that convincing? Absolutely not. Even if you add other valid and sound antinatalist arguments such as the lack of consent, risk aversion, rights violation, and of course the most important one – the harm to others, people won’t be convinced.

So why am I investing so much time writing about antinatalism if I think it is pointless to try and convince others to stop procreating? Because I am not aiming at the general public. I know they are hopeless. I am not trying to convince them to stop procreating, I am trying to convince you that procreation is such a serious crime – the greatest crime an individual can commit – that we must do much more than raise awareness. I am trying to convince you to skip the futile attempt of convincing all humans to stop breeding, and look for ways to make all of them incapable of breeding. People will never do it by choice. They will never stop breeding until we make them. It is not about finding the best antinatalist argument, it is about finding the best way to somehow sterilize them all.

References

Benatar, D. Better Never to Have Been (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006)

Benatar, D. Every Conceivable Harm: A Further Defence of Anti-Natalism

S. Afr. Journal Philos., 31 2012

Benatar, D. Grim news for an unoriginal position Journal of Med Ethics 35 2009

Benatar, D. Still Better Never to Have Been: A Reply to (More of) My Critics

Journal of Ethics (2013)

Bradley, B Benatar And The Logic Of Betterness Journal of Ethics & Social Philosophy 2010

Cabrera Julio, A Critique of Affirmative Morality: a reflection on death, birth and the value of life

(Brasília: Julio Cabrera Editions 2014)

Harman, E. Critical study of Benatar (2006). Nouˆs 43: 776–785.

McGregor, R & Sullivan-Bissett, E, ‘Better No Longer to Be: The Harm of Continued Existence’ South African Journal of Philosophy, vol. 31, no. 1, 2012 pp. 55-68.

Parfit, D. Reasons and Persons (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1984)

Shiffrin, S.V. Wrongful life, procreative responsibility, and the significance of harm. 1999

Legal Theory 5: 117–148

Leave a Reply