The following text is the second part of my comments on some of Julio Cabrera’s replies to questions he was asked in The Exploring Antinatalism Podcast #19 – Julio Cabrera ‘Questionaire on Antinatalism’. In this part I’ll address Cabrera’s replies to questions regarding: The moral status of animals, Abortion, EFILism, and Veganism.

For comments on his replies to questions regarding his general approach to Antinatalism please read part 1. And for comments on his replies to the question of involuntary sterilization please read part 3.

Question 18:

“It is true that your philosophical and ethical beliefs are unique but there are some unique principles you promote (such as the injunction against manipulation) that intuitively apply to animals as well. Do animals deserve any consideration in a Negative Ethics framework?

Can animals be harmed in similar way as you describe people can: the moral impediment, discomforts? What moral obligations or duties (for us, humans) follow from this?”

Cabrera:

“In my philosophy the animal issue is a less important point.”

“I actually start from an abyss between human and non-human animals. Here I followed two masters of the human condition, Schopenhauer and Heidegger.”

“In terms of my philosophy, the abysmal difference between human and nonhuman is already expressed in moral terms: nonhuman animals have no moral impediment. They are not open to the domain of morality; therefore, they cannot fail to be moral as human fail, they cannot be disabled for something in which they have never been enabled. This is sufficient to understand that we cannot have ethical-negative relationships with nonhuman animals; there can be no ethical relations between beings with moral impediment and beings without it. Therefore, there can be no “incorporation of animals into the moral community” in negative ethics.

However, in this ethics morality has two basic requirements, not to manipulate and not to harm. Although there is no reciprocity between human and nonhuman animals, we can say that we manipulate and harm nonhuman animals when we treat them badly, when we hunt and eat them, because they – at their own level – feel pain, fear, want to continue living, live comfortably, etc. but strictly speaking, we cannot say that we have moral relations with them; we can only be moral about them asymmetrically, but not together with them.

In Spanish and Portuguese there is a triad of similar terms that does not exist English, and that allows me to describe my attitude towards animals: trato, contracto, maltrato, treatment, contract and mistreatment.

We can only have contracts with other humans, because a contract requires moral (or immoral) interaction. But this must not lead to mistreatment. It is incorrect and disgusting to make animals suffer or kill for fun, but it is not “immoral”, because morality requires reciprocity; it cause us discomfort to see animals suffer, but not all discomfort is a moral discomfort. If we cannot have contracts with nonhuman animals, and we don’t want to mistreat them either, we must find some kind of treatment with them, which consists of not harming them and benefiting them if possible.”

Since sentience is the only relevant criterion for moral consideration, anyone who is capable of experiencing suffering should be included within the moral community. And since harms to sentient nonhuman animals matter to them as much as harms to humans matter to humans, sentient nonhuman animals matter morally no less than humans matter morally.

To exclude sentient nonhuman animals despite their possession of the only morally relevant criterion can only be merely due to their species, and that is Speciesism – a form of prejudice based upon morally irrelevant differences, which is no more justifiable than racism or sexism.

In the words of Richard Ryder, the psychologist who coined the term in 1970:

“All animal species can suffer pain and distress. Nonhuman animals scream and writhe like us; their nervous systems are similar and contain the same biochemicals that we know are associated with the experience of pain in ourselves. So our concern for the pain and distress of others should be extended to any ‘painient’ (i.e. pain-feeling) individual regardless of his or her sex, class, race, religion, nationality or species.” (Speciesism, Painism and Happiness Page 130)

The fact that it is morally wrong to exclude a group on the basis of an arbitrary criterion is Ethics 101.

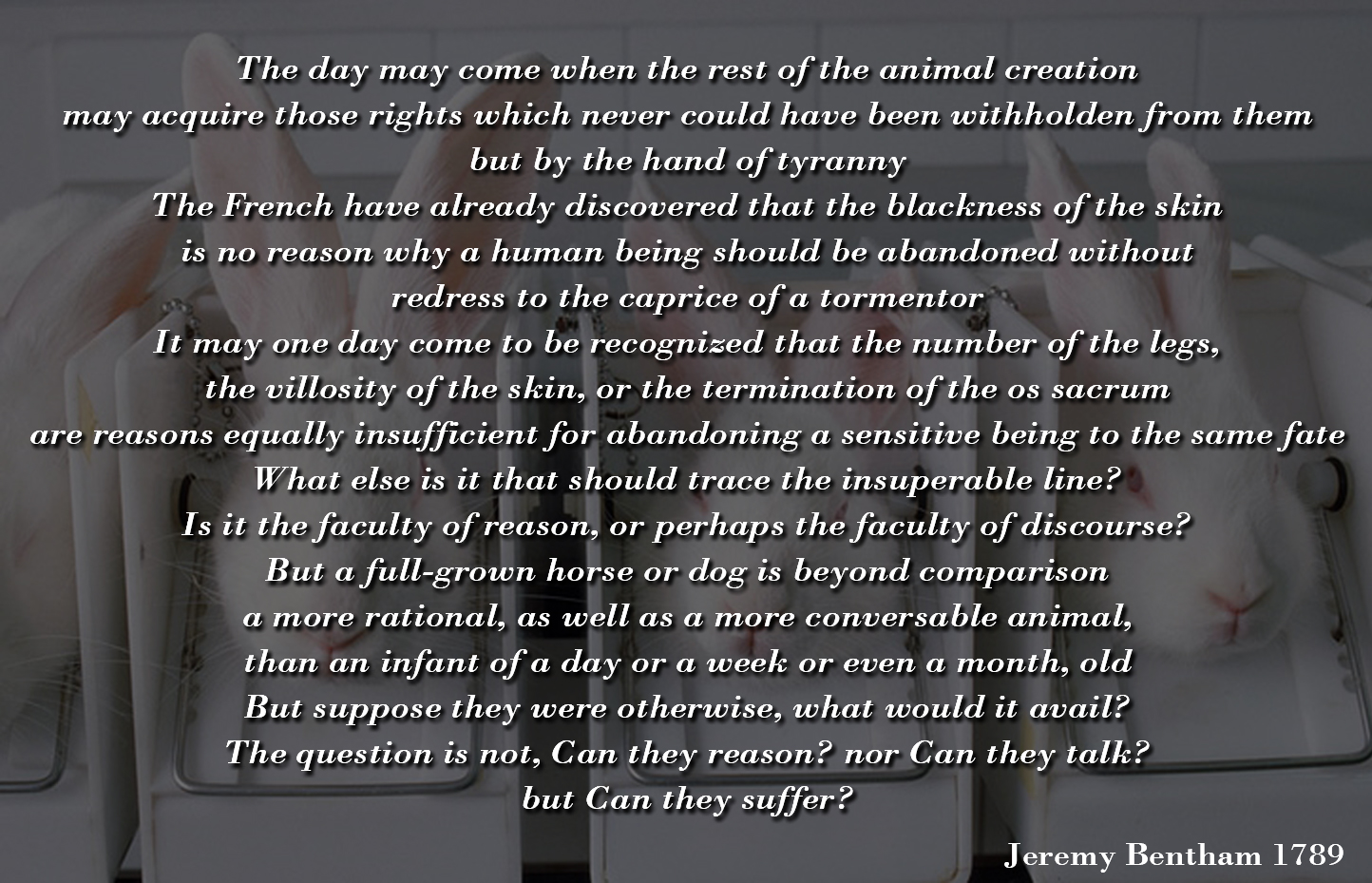

Cabrera’s claims were long ago refuted by Jeremy Bentham, as well as many others, especially Peter Singer. The following passage is taken from Animal Liberation and combines both of them:

“Many philosophers and other writers have proposed the principle of equal consideration of interests, in some form or other, as a basic moral principle; but not many of them have recognized that this principle applies to members of other species as well as to our own. Jeremy Bentham was one of the few who did realize this. In a forward-looking passage written at a time when black slaves had been freed by the French but in the British dominions were still being treated in the way we now treat animals, Bentham wrote:

The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?

In this passage Bentham points to the capacity for suffering as the vital characteristic that gives a being the right to equal consideration. The capacity for suffering-or more strictly, for suffering and/or enjoyment or happiness-is not just another characteristic like the capacity for language or higher mathematics. Bentham is not saying that those who try to mark “the insuperable line” that determines whether the interests of a being should be considered happen to have chosen the wrong characteristic. By saying that we must consider the interests of all beings with the capacity for suffering or enjoyment Bentham does not arbitrarily exclude from consideration any interests at all-as those who draw the line with reference to the possession of reason or language do. The capacity for suffering and enjoyment is a prerequisite for having interests at all, a condition that must be satisfied before we can speak of interests in a meaningful way.” (Animal Liberation Page 7)

I find Cabrera’s stance on nonhuman animals particularly weird and disappointing partly since he quotes philosophers such as Schopenhauer and Heidegger, who at least on this issue are not particularly relevant nowadays, despite that he knows Perter Singer. And I am not assuming that because Singer is one of the most famous moral philosophers of this current age, but since he quotes him in the book Introduction to a Negative Approach to Argumentation and in this questionnaire. Unfortunately, the quotes are about abortions and about intervention in nature, not about the moral status of animals, and that is quite a cheap cherry picking move by Cabrera, as although Peter Singer discussed many issues in practical ethics along the years, surly by far more than any other issue the moral status of animals is the one which is most identified with him, and surly Cabrera is familiar with his ideas on the matter, so the least he could have done is explain why he thinks they are wrong. I highly doubt that he could.

An intuitive counter response to Cabrera might be that actually nonhuman animals are the ones with which it is very easy for each antinatalist to assist by going vegan and by that reduce the number of created creatures, and by supporting spay and neuter of cats and dogs, and by donating to animal organizations whose activities practically reduce the number of created creatures for example. It is true that it is a very effective and easy way to practically promote antinatalism, but the main resistance to Cabrera’s stance should be general and ethical not personal and practical. His claims are simply speciesist and it needs to be said.

Countering his claim requires an embarrassing repetition of ideas, which I was sure are long ago behind us, such as the ones Peter Singer wrote more than 45 years ago.

It seems that Cabrera is mixing moral agency with moral patiency. Nonhuman animals may not be ‘open to’ the domain of moral agency meaning moral obligations don’t apply to them for the reasons that he mentions along his answer, but he doesn’t explain why nonhuman animals are not ‘open to’ the domain of moral patiency meaning moral agents do have moral obligations towards them.

Moral obligations are not necessarily about moral relationships, but about moral relations, meaning how we are supposed to relate to others. And that is supposed to be based solely upon the ability to experience, not upon the ability to be in moral relationships with others.

His stance is not only a groundless omission of every sentient creature who is not a human, but it is also supposed to be a groundless omission of every human who is mentally incapable of moral relationships such as infants, severely cognitively disabled people and etc., or in other words whom who are referred to as marginal cases of humanity. Once the criterion for moral status is the ability to be in moral relationships then the only way to nevertheless include marginal cases of humanity – people who can’t take moral responsibility – within the moral community is based on a morally irrelevant criterion which is their species. On the face of it, according to Cabrera, since children until a certain age and people with various mental issues are not open to the domain of morality they are not supposed to be the recipients of moral treatment. If Cabrera wants to include people who do not possess the relevant cognitive abilities that are required for moral relationships within the moral community, that can only be on the bases of speciesism. That would turn the criterion for moral status from ability to participate and understand moral issues into whom who were born a human. And that’s speciesism.

Most people don’t accept (even if unconsciously) the ability to be in moral relationships as a morally justified criterion for moral status. When it comes to humans, most people think that cognitive abilities are morally irrelevant and sentience alone is sufficient to grant all of them with full moral consideration. The only reason they exclude sentient nonhuman animals is speciesism.

Let’s examine the earlier quoted claim that Cabrera makes about Contractualism:

“We can only have contracts with other humans, because a contract requires moral (or immoral) interaction. But this must not lead to mistreatment. It is incorrect and disgusting to make animals suffer or kill for fun, but it is not “immoral”, because morality requires reciprocity; it cause us discomfort to see animals suffer, but not all discomfort is a moral discomfort. If we cannot have contracts with nonhuman animals, and we don’t want to mistreat them either, we must find some kind of treatment with them, which consists of not harming them and benefiting them if possible.”

Let’s say for the sake of the argument that to claim that something is disgusting doesn’t necessarily mean that it is immoral (a claim which is not very clear, certainly not when it comes to relationships with others, since when something is disgusting clearly there is something wrong with it), but it surly can’t be argued that something is incorrect yet not immoral.

It seems that Cabrera is a bit confused when it comes to nonhuman animals. He doesn’t want to support cruelty or to be indifferent towards it, but he refuses to include them in the moral community, and so he goes back and forth with the issue. According to the first paragraph nonhuman animals are excluded. According to the second paragraph nonhuman animals are included but asymmetrically. According to the first line in the third paragraph nonhuman animals are excluded, however on the next sentence they are included, and on the sentence after that they are included, but only to be excluded again right after that. Then he turns to some sort of an emotive argument claiming that animals deserve some kind of moral treatment because ‘it cause us discomfort to see animals suffer”, and not that animals’ suffering is morally wrong because it causes animals discomfort. In the end of this paragraph he leaves nonhuman animals excluded because they can’t have contracts with humans, and speciesistly suggests that we must find some kind of treatment with them if we don’t want to mistreat them, that is not because humans most certainly shouldn’t mistreat sentient nonhuman animals, but because humans don’t want to.

His groundless insistence on the need to have a contract with nonhuman animals in order for them to have a moral status becomes particularly ridiculous when he explains why he is against abortions, despite that obviously, if having a contract with other humans is the necessary criterion for moral status then fetuses most definitely shouldn’t be included in the moral community.

The issue of abortion is brought up in question 21 so I’ll jump to it now and later come back to his answers to questions 19 and 20.

Question 21:

The following are the four versions of questions regarding abortion that were presented in the Questionaire:

“Your ideas surrounding abortion seem to be counter-intuitive to many in the antinatalist community. Is a fetus a “moral person” that deserves to be free of manipulation? Does this moral personhood begin even before consciousness is possible?”

“I’d like to understand why he feels that abortion is a violation of the foetus’s autonomy if the foetus is not conscious and aware of its existence, and why the principle of not violating the ‘autonomy’ of something unaware of its own existence is more important than the suffering that would be prevented by aborting it.

This is something I find utterly baffling about Cabrera’s antinatalism, and I will be interested to hear if he can explain it – People have said he’s anti-abortion.”

“does he think it’s important to preserve the life of something that has not even developed a capacity to desire to exist?”

“Does he think preserving the life of a nonhuman animal which is more sentient than a human fetus – a fish, for example – is more important or less important than preserving the life of a human fetus? – why would preserving the life of a fetus be thought to be more important than 1, preventing the suffering that would be experienced as a result of the complete creation of a sentience, and 2, the desires of the unwillingly pregnant?”

“What are his views about anti-abortion laws? Does he think the unwillingly pregnant should be forced to stay pregnant by law?”

Cabrera:

“Whoever formulates the issue of abortion imposes his own approach in the very formulation. That the human must be defined by the appearance of consciousness is not a fact: it is a presupposition that we have the right not to assume. My anti-abortion argument from negative ethics is extensively exposed in my books. In this argument, the fact that the embryo or the fetus are not “people”, that they have no “conscience” or “desire to exist” are totally irrelevant. I adopt an ontological-existential notion of humanity, inspired by phenomenological-hermeneutical (in the next and last question, I speak of the difficulties that antinatalists read only analytical literature, dispensing with the “continental”). This specific ontological mode of the human is characterized by the fact that he/she was asymmetrically thrown into the world contingently and towards death. This happens long before the intellectual properties of awareness, self-awareness, rationality or language arise.”

If to continue the last line of thought from the previous question, the fact that the created person was asymmetrically thrown into the world contingently and towards death, can be said about nonhuman animals just as much yet, oddly, he deprives existing conscious and sentient nonhuman animals of moral status but grants fetuses with one.

And it gets even odder as it is not even the fetus itself who is granted with moral status despite not being conscious and sentient while existing conscious and sentient nonhuman animals are not, but it is the ontological-existential notion of humanity which is granted with moral status despite it not even being a morally relevant entity. The ontological-existential notion of humanity can’t feel, it doesn’t experience anything, it can’t be deprived of anything, yet according to Cabrera not only that this notion is a moral entity (and existing conscious and sentient nonhuman animals are not), it is in the center of his anti-abortion argument, and it justifies the creation of a person in case of conception, since the ontological-existential notion of humanity already exists, and terminating it by abortion is to manipulate it. Obviously, according to Cabrera not having an abortion is to manipulate the created person, therefore, given that he is anti-abortion, we must conclude that to manipulate the ontological-existential notion of humanity is morally worse than to manipulate an actual person.

Any sentience level is sufficient for someone to be morally considered, so there is no need to go as far as to the most intelligent social mammals, but I will go that far just to show how ridiculous this argument is, to compare an adult female elephant living in a complex fission-fusion society, being highly curious, aware of death, have a tremendous memory, great ability to solve problems, and etc., not even to an insentient heap of cells, but to the abstract notion of humanity, is to redefine speciesism. How disrespectful towards nonhuman animals’ actual experiences can one be to seriously consider merely the abstract ontological-existential notion of humanity as a moral entity, but not any nonhuman animal?

This claim remains very odd even if we’ll accept for the sake of the argument that notions can be treated as moral entities, because Cabrera himself argues that the ontological-existential notion of humanity is horrible and immoral, since, among other things, each person is “asymmetrically thrown into the world contingently and towards death”. And here are three more examples taken from his book Discomfort and Moral Impediment:

“Procreation is a structurally unilateral act in which one of the parties involved is brought to life by force through the action of others who decide that birth as a function of their own interests and benefits, or as a consequence of negligence”. (p. 129)

“Upon being born, we are thrust into a temporal process of gradual consumption and exhaustion characterized by pain (already expressed by a newborn baby’s crying when faced with the aggressions of light, sounds and the unknown), by discouragement (not knowing what to do with oneself, with one’s own body, with one’s own desires, something that babies will begin to suffer shortly after their birth); and lastly, by what I will call moral impediment, meaning being subjected to the pressing and exclusive concern with oneself and the necessity of using others for one’s own benefit (and being used by them).” (p. 25)

“As we are thrust into a world affected by structural discomfort, submitted to pain and discouragement and forced to act in an entangled web of actions within small spaces and under pressing time, we cannot avoid harming other humans in concrete situations of the intra-world, even those who we intend to help or benefit. At certain points in time, we are all provokers of harm. In an existential sense, we contribute to the discomfort of others.” (p. 66)

Hence, it would make more sense that if anything, his perceptions would intensify the argument for abortion, not establish claims against it.

But Cabrera insists:

“What is relevant to our question here is that since the moment of conception in a human body, we already have an existing one thrown over there, contingent, meaningless and towards death, even if this being has no first person awareness of that condition, nor any defined identity. In my own terms, it is a terminal human thing that has already begun to end, not potentially, but now.”

But who is the victim of this condition before that person has first person awareness? Who is harmed by the fact that a heap of cells have already begun to form? All the more so what’s wrong with ending it before that heap of cells has first person awareness, especially considering that it is necessarily a case of “an existing one thrown over there, contingent, meaningless and towards death”?

Since the issue is of abortion, it means that the parents do not wish to create a person, at least not in that current pregnancy, so they are not the victims of the abortion as they want it. If anything they would be the victims of not having an abortion, because they would be forced to create a person against their will. Does the ontological-existential notion of humanity overpower their interests as well? And more importantly, given that creating a person is not only creating a subject of harm, but a small unit of exploitation and pollution, the question mustn’t only be is it justified that people would be imposed to create a person against their will, since “since the moment of conception in a human body, we already have an existing one thrown over there, contingent, meaningless and towards death”, but also is it justified that numerous existing conscious and sentient nonhuman animals would be harmed by another unit of suffering, exploitation and pollution since “since the moment of conception in a human body, we already have an existing unit of suffering, exploitation and pollution thrown over there, contingent, meaningless and towards death”? Since it is never justified, procreation is never justified, and abortion always is.

How can a notion be morally more important than the real interests of real people – the parents who decided that they don’t want to create that person, and the interests of the main victims of most procreations – all the nonhuman animals that would be hurt if abortion doesn’t take place?

Cabrera tries to explain:

“Benatar claims that “coming into existence” cannot be determined only biologically. I totally agree with him. In my approach, this terminal being and “towards death” aroused in the conception is not experienced, of course, in the first person, but is seen in the second and third person by the others involved. The humanity of a human is not just something given biologically, but also something socially constructed. The others will be able to confer or refuse human status to what is, for now, a heap of cells. They are capable to give the embryo and the fetus their humanity or refuse it. The procreated may or may not be part of the moral community depending on the decision of these third parties. Humanity does not need to be experienced in the first person to be recognized.

In these terms, what is immoral about abortion? When you have an abortion you eliminate in a manipulative and unilateral way someone else’s terminality, even if it is not yet a determined person. Even though – in the pessimistic perspective that I endorse – life is something terrible, we have no right to decide for another being that is already as terminal, absurd and thrown in the world toward death as we are. In this line of argument, abortion is immoral because it is a manipulative act, done for our convenience and offensive to an autonomy that is in the present recognizable in the third person.”

Resisting abortions is not considering the interests of third parties, but crushing the interests of first parties as created people never asked to be born, never gave consent to be harmed while existing, and are imposed with a constant risk of a miserable life, and it is crushing the interests of second parties, meaning the ones who would be mostly and most directly affected by the decision not to have an abortion, and these are the person’s parents, and much more than them – everyone who would be harmed by that person all along its existence.

Would he argue that by saving someone else’s life we eliminate in a manipulative and unilateral way someone else’s terminality? If we prevent someone’s murder is it also considered by his terms to eliminate in a manipulative and unilateral way someone else’s terminality?

And why is the notion of terminality morally more important than actual harm to actual sentient creatures? Again we encounter his odd priorities, as the notion of manipulation is prioritized over suffering. And in this case it is not even the manipulation of the created person, or of the created person’s parents, or of the created person’s victims, but the manipulation of an autonomy that is in the present recognizable in the third person. So the abstract notion of autonomy, which is merely present in some of the least affected people, defeats everything else. Does this line of thought work with other issues as well? Does the abstract notion of racism, which is merely present in some of the least affected people, defeat everything else as well?

Was the abolition of slavery immoral because it was a manipulative act, done for salves’ convenience and was offensive to the autonomy of the notion of white supremacy that was recognizable in the third person? What right do we have to reject the notion of white supremacy? Is it because white supremacy is most definitely morally wrong? Well, isn’t procreation most definitely morally wrong even according to Cabrera himself?

But Cabrera is sure that everyone who wonders how he can be anti-abortion is missing something:

“People who read my writings without due attention, wonder how can one be antinatalist and anti-abortion at the same time. After all, if life is so bad, do we have a duty to prevent more humans from being thrown into this terrible world? But this is a very simple-minded argument. If we think more carefully we can see that the situation of procreation and the situation of abortion have different logical and ethical structures.

In abstention we think from nothing, while in abortion we think from something. In the case of abstention there is nothing about which we have moral dilemmas before which we must stand. We can say that while procreation is preventable medicine, abortion is therapeutic medicine; and nothing can make abortion preventive.

Therefore, in the case of abstention, it is the consideration of the terrors of existence that prevails over autonomy, because there is no autonomy to respect (unless conjectured, with all the problems that this entails). In the case of abortion, the respect for autonomy prevails, an autonomy that already exists in the third person as a social and interactive fact.”

In abstention we don’t think from nothing, but also from something, that is from a place of resistance to create a person in the better case, or from a specific lack of want to create a person in the less good case. The case of abstention is thinking from something and not from nothing, it is at least thinking from something undesirable if not unacceptable. Once someone is in the position of abstention it means that that someone wishes to abstain from creating someone, and that is thinking from something.

In both cases there is a notion of humanity, in the case of abstention people are trying to prevent it, and in the case of abortion they are also trying to prevent it. The only difference is biological, and ironically Cabrera is the one who claims that abortion is not a biological issue.

Besides, isn’t abstention supposed to be, according to Cabrera, a manipulative act done for our convenience, and offensive to an autonomy that is in the present recognizable in the third person as well? I think it is, since clearly people choose abstention exactly because they have a notion of humanity which they wish to avoid, in general, or specifically in that given sexual act. So, is any use of contraception a manipulative act, done for our convenience and offensive to an autonomy that is in the present recognizable in the third person? Cabrera claims that the humanity of a human is not just something given biologically, but also something socially constructed, if that is the case we don’t need a heap of cells for abortion to be morally wrong, the very idea of creating a human is sufficient, and therefore isn’t any use of contraception morally wrong because it is a manipulation of the notion of humanity? Isn’t every case of people choosing not to breed a manipulation of humanity? As what do people who choose not to breed actually say, that they can create a human and choose not to, how isn’t that a manipulation of the notion of humanity?

There is, no incongruity at all in being antinatalist and anti-abortion; on the contrary: if the accent is put on manipulation (as is the case with negative ethics), it is almost mandatory to be both; because the same type of manipulation appears, only in opposite directions: when the child is desired, it is manipulated in procreation, and when it is unwanted it is manipulated in abortion; in both cases the terminal being is treated as a thing.

Only that in one case there is a harmed person, harmed parents and numerous harmed creatures who the created person would harm along its life, and in the other case the “victim” is the notion of humanity. We have a very serious and certain harm on one side, and none at all on the other.

By the way, most of acute opponents of abortion don’t fight it in the name of humanity but in the name of god. It is not the manipulation of humanity which they are concerned about, but the manipulation of god. Now since there isn’t one, there are no real victims of abortions. On the other hand, there are plenty of victims to each and every case that abortion wasn’t performed.

Cabrera argues that the created person should have the opportunity to decide later what to do about being thrown into the terrors of the world:

“It is true that by not aborting we throw this being into the terrors of the world, but at least, late on, this terminal being will be in a better position to decide what to do with its terminality; this will not be entirely decided by the others.”

No, it is anyway entirely decided by others. Only that in the case of abortion others decide that a person won’t be created and therefore won’t be harmed and harm others, and in the case that abortion wasn’t performed, it is others who decide that a person would be created and therefore be harmed and harm others.

Because of life’s addictive element, a created person doesn’t really decide what to do with its terminality, but is prone to continue living and therefore to suffer, vainly hoping that someday things would get better. Something that is very unlikely to happen.

Besides, there are no real better “positions” to decide what to do with one’s terminality. It is impossible to undo existence. Existence can’t be canceled. One cannot retroactively erase its own existence, only to end it, but there is no good exit plan. Suicide is a terrible exit plan because even people who really suffer in life are usually afraid of death, of pain, of permanently disabling themselves if they don’t succeed, of committing a sin, of their family, of the unknown, of breaking the law, of being socially shamed, of being blamed for selfishness, of the isolation ward in a psychiatric hospital and etc. So the suicide option is not very tempting in the better case, and nonviable in the worst.

It is false from every perspective to present suicide as a legitimate option available to anyone at any time. Biologically, suicide is the last option. And the fact that people are biologically built to survive, doesn’t soothe individuals whose lives are not worth living in their eyes, but exactly the opposite. They are prisoners of their own biological mechanisms. They are life’s captives, not free spirits who can choose to end their lives whenever and however they wish. People are trapped in horrible lives without a truly viable option to end it.

People have no serious exit option that can justify their forced entry. Not that if there was any, procreation was morally justifiable (as it still necessitates the suffering until the decision to end life is made), but at least this part of the argument was decent and coherent. But there isn’t an exit option so it is not. People must overcome too many obstacles with each being too difficult, for suicide to really be an option.

No one should put anyone in such a horrible position where they don’t want to live but are trapped in life.

Tens of millions of people are forced to live day after day after day, feeling that they don’t want to live, but are afraid of carrying out suicide, or that they are even in a deeper trap, can’t stand living but can’t stand the thought of hurting others by killing themselves. This is the cruel trap many people are forced to endure because they were created. The option of suicide is not a legitimate solution for the problem of procreation, but in fact another of its many evils.

But when it comes to actual cases he is less determined and more ambiguous:

“Anyway, there is no logical sequence form (I) abortion is immoral to (II) one should never abort. For we can be totally convinced of the immorality of abortion, but understand that, in many dramatic cases, women had to abort. Negative ethics is limited to saying that, as understandable as this act may be, these people will be doing something ethically wrong. Whoever aborts is certainly not a criminal (as the anti-abortionists sometimes rhetorically proclaim), but neither can we say that they are totally morally correct people.

I suppose that in order to solve the dramatic cases, it may be better to resort to some utilitarian or pragmatic procedure, even if the immorality of abortion is theoretically recognized (in my line of argument or other).”

What does it mean whoever aborts is certainly not a criminal but neither can we say that they are totally morally correct people? And what are according to him dramatic cases? Does he mean cases of rape? Extreme poverty? Foreseen severe impairments? All of the above? And isn’t the notion of humanity manipulated in these cases as well? Could it be that terms such as ‘suffering’ and ‘justified’ somehow have found their way into the discussion when he needed to approve some cases of abortion?

It’s clear to him that he cannot oppose abortions on every case so he permits the ones he calls dramatic cases, but without detailing why and which cases are dramatic.

It seems that when he needs to encounter a real issue from real life, he ditches his ideas of negative ethics and suggests that “it may be better to resort to some utilitarian or pragmatic procedure”. But why? Is it because he knows that he cannot look in the eyes of a raped woman and tell her that she must raise the child of her rapist because otherwise it would be to manipulate the notion of the child’s humanity? And isn’t an ethical theory supposed to address all cases and if not, to at least coherently explain why some cases are exceptional?

Cabrera realizes that his ideas are not really perfectly viable and so he pulls his perspectivistic approach:

“This line of argument is perfectly viable and it will be seen as “counter-intuitive” only if the other parts impose their own assumptions; assuming mine, my posture is perfectly intuitive and theoretically sustainable. As I am also a logical pessimist, I do not believe in absolute conclusions. What I presented here was just a line of sustainable argument. Abortion can be morally legitimate in one line of argument and morally illegitimate in another. We don’t need to destroy each other because of that.”

But for whom who is forced to be created, for whom who is forced to create, and for whom who are forced to be harmed by the created, procreation is indeed extremely destructive.

Question 19:

The following are the four versions of questions regarding EFILism that were presented in the Questionaire:

“Are you familiar with the subject of EFILism, and if so do you think about it? EFILists essentially believe that sentient life should be placed in plaintive care, in hospice so to speak, and that there should be direct intervention in ending wild life suffering, even if the only option is to find a way of euthanizing them. What are your thought on that? I believe that Antinatalsim/EFILism are essentially the final civil rights movement – that there is nowhere for the subject of suffering mitigation to go from there, and that not being imposed upon to exist can and should be seen as a sentient creatures most supreme civil rights. What do you think of this idea?”

“Do you believe that the concept of Antinatalism should be extended to all sentient creatures? Do you believe that a goal of Antinatalism should be the extinction of both humans and animals? I feel it would be the greatest tragedy we could allow, for humans to go extinct before the animals, nature is where most of the suffering is on planet earth – thoughts?”

“Have you thought about extending your ideas about antinatalism to the whole of animal kingdom? Jeremy Bentham asked “the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? But, can they suffer?” today we know the answer. Animals do suffer. What can we do about that? What are Cabrera’s thoughts on wild-animal suffering and that there would be much more of it if only humans went extinct?”

“Would you extend antinatalism to nonhuman animals as well? There is an enormous amount of suffering in the nonhuman world, do we have an ethical duty to end that suffering? What can we do knowing that people will still be procreating? What can we be doing knowing that the antinatalist project will never come to be? Does that also extent to animal rights?”

Cabrera:

“As we saw in the previous question, in negative ethics we cannot have ethical relations with animals, as they have no moral impediment. Therefore, if negative ethics were in agreement with the extinction of nonhuman animals, it could not be for ethical reasons, strictly speaking. That is why I would not accept this idea of “extending” the ethics of humans to nonhumans; because as they have ontologically different ways of being, there is nothing to “extend”; the attitude towards nonhuman animals must be invented post-morality in a particular way.

Leaving aside the contract, which is impossible, we are left with treatment and mistreatment. We have to see if the extinction of nonhuman animals could be included in treatment, or if the extinction would generate some kind of mistreatment. If the first were possible, negative ethics could approve the procedure. But if in order to extinguish them we had to mistreat them some way, negative ethics cannot accept to suppress nonhuman animals, even if the extinction is intended to be “for their own good”.”

The implication of this stance is that since humans cannot have ethical relations with animals, but they can mistreat them (and I’ll ignore for the sake of the argument the contradiction between these two statements), then even if all that it would take to end all the suffering that every nonhuman animal that would ever exist, is the pain of one pinprick for each currently existing nonhuman animal (which quantitively speaking is just a fraction of the number of nonhuman animals that would ever exit), Cabrera would oppose it because that would be humans mistreating nonhuman animals. That means that the actual experiences of the infinite number of sentient creatures that would exist if humans don’t inflict the pain of one pinprick for each currently existing nonhuman animal, are worth so little in his view, that the abstract virtuousness of humans undoubtedly overpowers it. And that is undoubtedly one of the cruelest ideas I can think of. Obviously, unfortunately that scenario is absolutely delusional but it is ethical. There is nothing better or a more important goal than ending all the suffering of all the creatures in the world. Apparently not according to Cabrera. He rather that an infinite number of nonhuman animals would endure life of suffering than the option that much less humans would allegedly mistreat much less nonhuman animals.

But ethics should first and foremost be concerned with actual suffering of anyone who is capable of experiencing it, not with the supposed incorruptibility of one species, especially since it is irrelevant to the sufferers. Ethics should focus on pain and distress wherever they happen and to whomever. It should be concerned with the actual cruel fates of the victims, not with the fictional purity of the moral agents.

It seems however, that Cabrera is more bothered with what humans would do than with what would happen to infinitely more nonhuman animals.

And it shouldn’t come as a surprise since as we have seen in his explanations of his basic stands regarding antinatalism, he is focused on the ontological position of humans, not on the actual experiences of the rest of the sentient creatures in the world. The fact that this world is actually a planetary scale restaurant, in which everyone is suffering, is not his motive. His drive is not the suffering but the ‘ontological-existential notion’, and not of everyone but of one species only.

Here is an example from the very same answer:

“Ultimately, I consider humanity as the primordial biological catastrophe of nature and think that life is not so calamitous if it does not have reflexive self-awareness.”

“…hence the animals’ unconcern and tranquility, so worthy of envy. Animal suffering is much more integrated with nature; it is not enough to say, like Bentham: ‘they also suffer’.”

“I really wouldn’t have a problem with a planet without humans and with nonhuman animals living in their natural surroundings. What did not work is the human life; the other animals are fine as they are and would be much better off without the suffering introduced by humans.

God should have stopped creation before the sixth day. It would be good to leave nonhuaman animals in their lives of harsh survival and spontaneous violence. It is true that humans care for animals and protect them from certain hostile environments. But it is also true that they hunt, eat and mistreat them. I think the best thing we can do for animals is to disappear and leave them alone.”

The issue of self-awareness among nonhuman animals is factually and morally controversial. Only a speciesist would put all the nonhuman animals under the same category despite that clearly the similarity between other social mammals (let alone other primates) and humans, is far greater than the similarity between social mammals and sponges or earthworms, and yet, earthworms and orangutans are on the same group, and humans are on a whole different superior level. That is factually ridiculous. And it is factually noncontroversial that at least some social mammals are self-aware. But I don’t want to discuss it even if it serves the cause, because it is morally irrelevant and therefore wrong to focus on that. We can say that self-awareness can actually in many cases sooth and not enhance negative experiences, for example when one is aware that one’s injuries or maladies are not dangerous and easily treatable. That is as opposed to creatures who suffer from similar conditions but are unaware of their condition and therefore suffer more. But again, that is irrelevant in terms of moral status. Being self-aware to the fact that I am suffering right now is not necessary to establish my moral status. The fact that I am suffering is sufficient. I don’t need the ability to self-reflect on my negative experience for it to be negative. The ability to have a negative experience is sufficient.

Experiencing extreme fear every single time someone goes out of the cave to drink is horrible for anyone who experiences it, without being self-aware that extremely fearing every single time someone goes out of the cave to drink is horrible. This experience is horrible without reflecting on its horribleness. Extreme fear needs not reflexive self-awareness to be horrible. It is horrible as it is. Fear is fear, and pain is pain. One doesn’t need to have reflexive self-awareness to feel fear and pain. Not reflexive self-awareness is the crucial component in moral status but sentience. What really matters in morality is not self-awareness but the experience of pain and suffering.

So it is most definitely enough to say, like Bentham that they also suffer.

And the claim that “animal suffering is much more integrated with nature” is a super-anthropocentric, speciesist, nature worshiping, and extremely ignorant claim.

To claim that other animals “would be much better off without the suffering introduced by humans” is probably one of the greatest understatements ever made. And the claim that “other animals are fine as they are” is probably one of the greatest misstatements ever made.

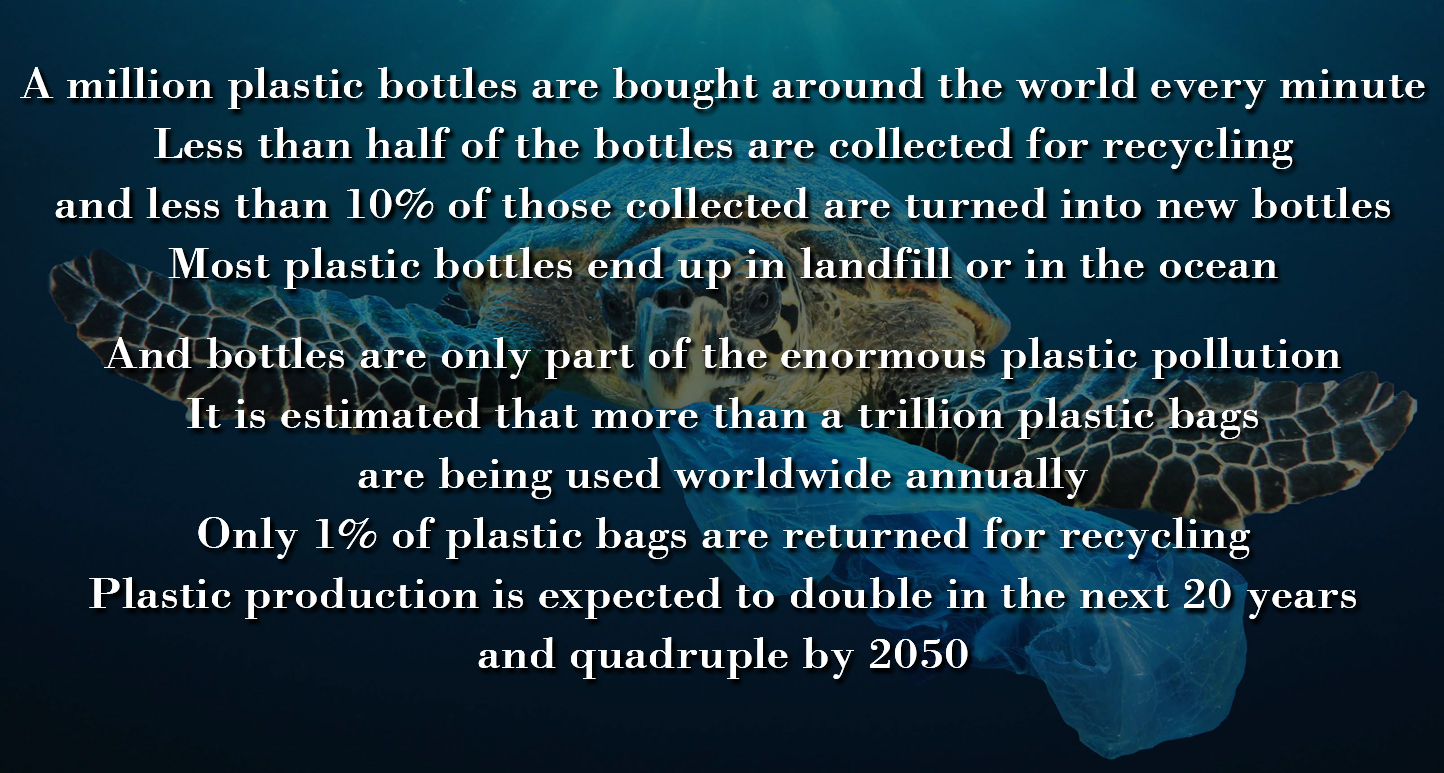

As argued elsewhere, procreation is a very serious crime because the ample evidences that bad experiences are more important than good ones, not only serve as a proof that good experiences are at least not as good as bad experiences are bad (if not proving that bad experiences almost always outweigh the good ones), but how horrible life actually and inherently is. Basically, pain and other negative experiences increase the fitness of individuals by enhancing their respondence ability to threats to their survival and reproduction. It has a crucial adaptive function. Existing sentient creatures are tortured by evolutionary mechanisms which their only point is that additional sentient creatures would exist, regardless of any of those creatures’ personal wellbeing. It is a pointless, frustrating and painful trap.

Probably the strongest evidence for that, and one of the strongest arguments for including animals living in nature in antinatalism, is that by far the vast majority of individuals in nature never reach adulthood, with most living short lives of nothing but fear and pain.

Most people, and disappointedly it seems that Cabrera is among them, think of mammals when they contemplate about nature. But even among mammals – the class with the highest survival rates – the vast majority of individuals never reach adulthood. And by far most of the individuals in nature are not mammals. The reproductive strategy of by far most of the species in nature is r-selection, meaning that most animals reproduce between hundreds to hundreds of thousands of children (some even millions), with usually only few who reach adulthood, and only two who survive long enough to reproduce (that is the case in any stable population since otherwise we would have seen a massive population increase).

Obviously what matters morally is suffering, not adulthood rates. But behind the astonishing survival figures in nature, which reach less than one percent among many species (probably most), are innumerable suffering individuals who experienced nothing but suffering in their short brutal lives. It goes to show how dispensable sentient individuals lives are in nature. The fact that most of the creatures who are created in this world are born only to suffer is not only absolutely natural, but is nature in its essence. And so, probably most relevantly to antinatalism, is that in the case of animals in nature there should be absolutely no doubt that for the absolutely vast majority of creatures, coming into existence is a very serious harm.

As I argued earlier, I don’t think that from all the philosophers and other thinkers, Schopenhauer is the one to be based on when it comes the status of nonhuman animals, but if he chose to rely on him in this context, he should be reminded of another Schopenhauer’s quote:

“A quick test of the assertion that enjoyment outweighs pain in this world, or that they are at any rate balanced, would be to compare the feelings of an animal engaged in eating another with those of the animal being eaten.”

And this claim is an even much stronger support of EFILism when considering that no animal is engaged merely in eating another, but with very many anothers, and that no animal being eaten is merely suffering from being eaten alive but from many other factors such as hunger, thirst, cold, heat, diseases, parasites, fear, fatigue, worn out and etc.

Despite all the things he said so far all along the questionnaire, he also argues that:

“The extinction procedure, even inspired by this beautiful purpose, can generate suffering in the animals that we are trying to benefit, within a macro project, can make them suffer. Maybe it would be necessary to create concentration camps for nonhuman animals; it would not be a peaceful procedure.”

But why does he call it a beautiful purpose if he claimed that “the other animals are fine as they are” and that “the best thing we can do for animals is to disappear and leave them alone”?

And why does he call it a beautiful purpose if there are no moral relationships with nonhuman animals? Shouldn’t he view it as neutral? If it is not neutral but good to end nonhuman animals suffering how is it not a moral requirement? How is it not even a moral issue given that he previously argued that there are no moral relationships between humans and nonhumans? He can counter-argue that we don’t have an obligation to save all the animals but it still is a beautiful purpose. But the reason it is a beautiful purpose is because it is the moral thing to do, or at least it is morally good to do so. And if a purpose is beautiful (moral) then we need to try and implement it, not state that it is beautiful. Beautiful purposes need to be practically actuated.

Unfortunately I agree that this beautiful purpose can’t be implemented by a peaceful procedure, but much more unfortunate is that I don’t think it can be implemented at all. I elaborate about this in the text about Efilism, but anyway this point is irrelevant to this discussion since my reservations about this purpose are only practical and by no means ethical. In my view moral duty stems from vulnerability not from relationships. We are morally obligated to help any vulnerable subject if we can, regardless of the species of the vulnerable subject or our relationship with the vulnerable subjects. Sentience is a sufficient criterion for moral status and a sufficient justification to try and prevent harms inflicted on any vulnerable subject. So obviously we must try to prevent any harm from any vulnerable subject, no matter who s/he is and where s/he is.

And obviously we most certainly mustn’t inflict harm on other vulnerable subjects, and since everyone always do, even the ones who are not eating animals or animal based products, everyone mustn’t procreate. No matter who someone is, where and how that someone lives, eventually everything is somehow at someone else’s expense. Existence is harmful and existing is harming. Negative ethics more than any other moral theory should be EFIList. It isn’t, only because it is speciesist. A non speciesist antinatalist approach must be EFIList. Or in other words, EFILism is antinatalism without speciesism.

Place suffering in the center of negative ethics and expend it beyond humans to every sentient creature on earth and you actually have a form of EFILism. There is more than one road to EFILism but this is certainly mine. That’s why when I first read A Critique of Affirmative Morality I thought that I finally found my “bible”. I still think it is a great book which is most definitely worth reading by any antinatalist let alone EFIList. However reading other texts by Cabrera, especially Introduction to a Negative Approach to Argumentation, and his answers to this questionnaire, made me realize that the problem I had with negative ethics go deeper than its feeble conclusions. There is no way around it, Cabreara’s Negative Ethics is speciesist.

I am talking with people about moral issues, especially of harming nonhuman animals for a long time now so I am used to their infinite moral flexibility when it comes to ideas they don’t want to embrace, but I didn’t expect that from the philosopher who wrote the book A Critique of Affirmative Morality. At that point I thought that the only reasonable explanation for his unequivocal senseless immoral excuses is that he doesn’t want to embrace veganism. And indeed came his awful answer to the question about veganism.

Question 20:

Many (but not all) antinatalists are vegans due to the incorporation of animals into their moral community. Are you a vegan? Irrespective of the answer: why? Why he isn’t vegan? If forcing nonhumans into the world for human consumption or to any other benefit compatible with antinatalism? And with that is there an ethical duty for antinatalists to be vegan and not pay for others to be brought into the world for their benefit?

Cabrera:

“As there is no possibility for me to incorporate animals into the moral community THAT cannot be the reason for being vegan or vegetarian. I have said before that this provide no reason to mistreat animals. The problem is that it seems evident that we mistreat them when we kill them for food. Therefore, it seems that we should radically refuse to feed on them.

I am not particularly vegan or vegetarian, although I completely eliminated beef, pork and fish from my diet many years ago; but I eat chicken often. This would seem to be a clear contradiction between my thinking and my life. Even though we cannot have ethical relationships with animals, and even though I am not concerned with extinguishing them, I agree with not mistreating them, and eating them clearly seems to be a kind of mistreatment.

The first argument to come out of this blatant contradiction is that I may need to eat some meat to preserve my health. The thesis that one can live in good health without eating animal proteins is controversial. I have consulted all kinds of medicines, orthodox and heterodox, and the opinions are the most varied, although each part affirms with total certainty to be right. On the other hand, one cannot speak generally of “human health”, but of individual bodies; what is not necessary for certain organisms may be necessary for others.

In my particular case, I feel weak and sleepy if I don’t eat some chicken meat for several days. Accepting that completely suppressing the consumption of some meat was clearly bad for my health, should I take the requirement not to mistreat animals to the point of damaging my health?

In negative ethics, we have no moral obligation to preserve our life or our health just to continue living; we can and must risk our lives because of some ethical requirement. But since we have no strictly ethical obligations to nonhuman animals, it would seem that this requirement to harm me in order to preserve them cannot be ethically justified. Nevertheless, we decided not to mistreat non human animals, but since this is not a moral principle, but only a beneficial practice, we can have the right to balance it with other morally relevant considerations, not to take it as a requirement without exception.

If I choose to preserve my health by continuing to eat birds, I could claim that I need my health not for satisfying frivolous gastronomic pleasures or for gluttony, but for to be able to continue doing things that I consider as morally important as the act of not eating animals; for example: fighting injustices, defending social movements, finishing a book against racism or doing activism in the antinatalist cause. I cannot assume a fanatic vegetarianism; I would have to consider, in specific cases, what are the social costs – not just personal, selfish or hedonistic – of stopping eating meat entirely. We cannot escape “spciesism” by falling into a kind of “animalism”; in some cases we may have to favor human animals and in others our option will be for nonhumans ones.”

Since I found his health excuse utterly insulting, I will not focus on nutritional matters here. I am anyway sure that it is totally needless for any of the readers of this text. The fact that everyone can maintain healthy life on a plant based diet is, as opposed to his claim, not controversial. Like the philosophers he chose to quote so to base his speciesist stands on the moral status of nonhuman animals, his nutritionist basis is also irrelevant and outdated.

Anyway, it is more interesting and relevant to focus here on veganism and antinatalism from his negative ethics perspective.

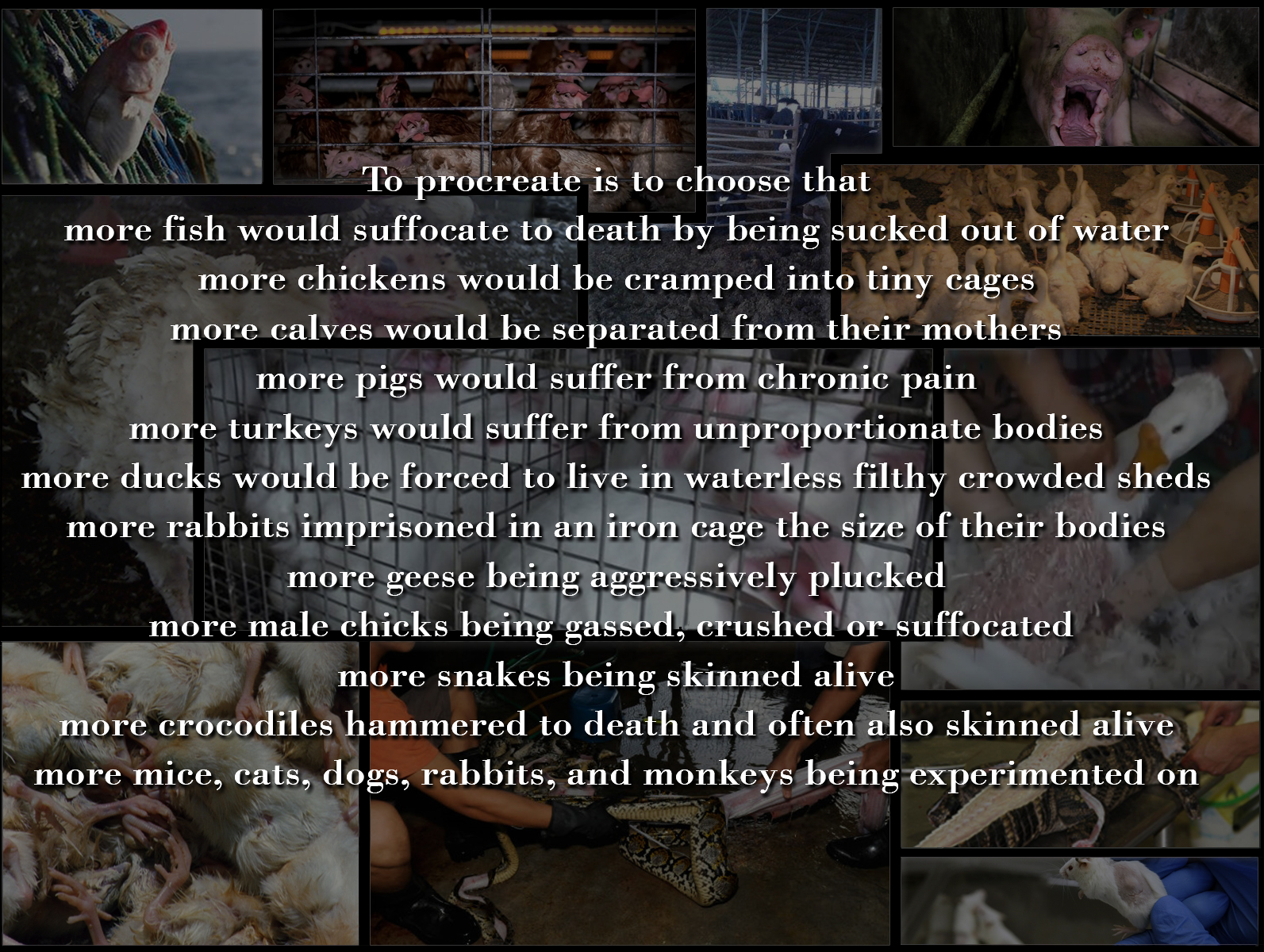

If antinatalism is an opposition to the imposition involved with the creation of a vulnerable person without consent and while risking that person having a miserable life, then when it comes to animals in the food industry, there is no doubt that it is an imposition that involves the creation of a vulnerable creatures without consent, and it is not risking them having a miserable life, but insuring that they would have miserable lives full of abuse and torture.

Antinatalists justly refuse to impose harm on a person without obtaining that person’s consent, but the ones who are not vegan unjustly agree to impose harm on numerous animals without obtaining their consent. They don’t obtain their consent to be genetically modified so they would provide the maximum meat possible. They don’t obtain their consent to be imprisoned for their entire lives. They don’t obtain their consent to live without their family for their entire lives. They don’t obtain their consent to suffer chronic pain and maladies. They don’t obtain their consent to never breathe clean air, walk on grass, bath in water, and eat their natural food. They don’t obtain their consent to be violently murdered so that people could consume their bodies.

Animals exploited in the food industry are the most unequivocal example of sentient creatures who are forced to live in extreme misery during every single moment of their lives. In their case, extreme misery is not a risk that anyone involved in their creation is taking, but a decision. In their case, creation is not a Russian Roulette but a certain living hell.

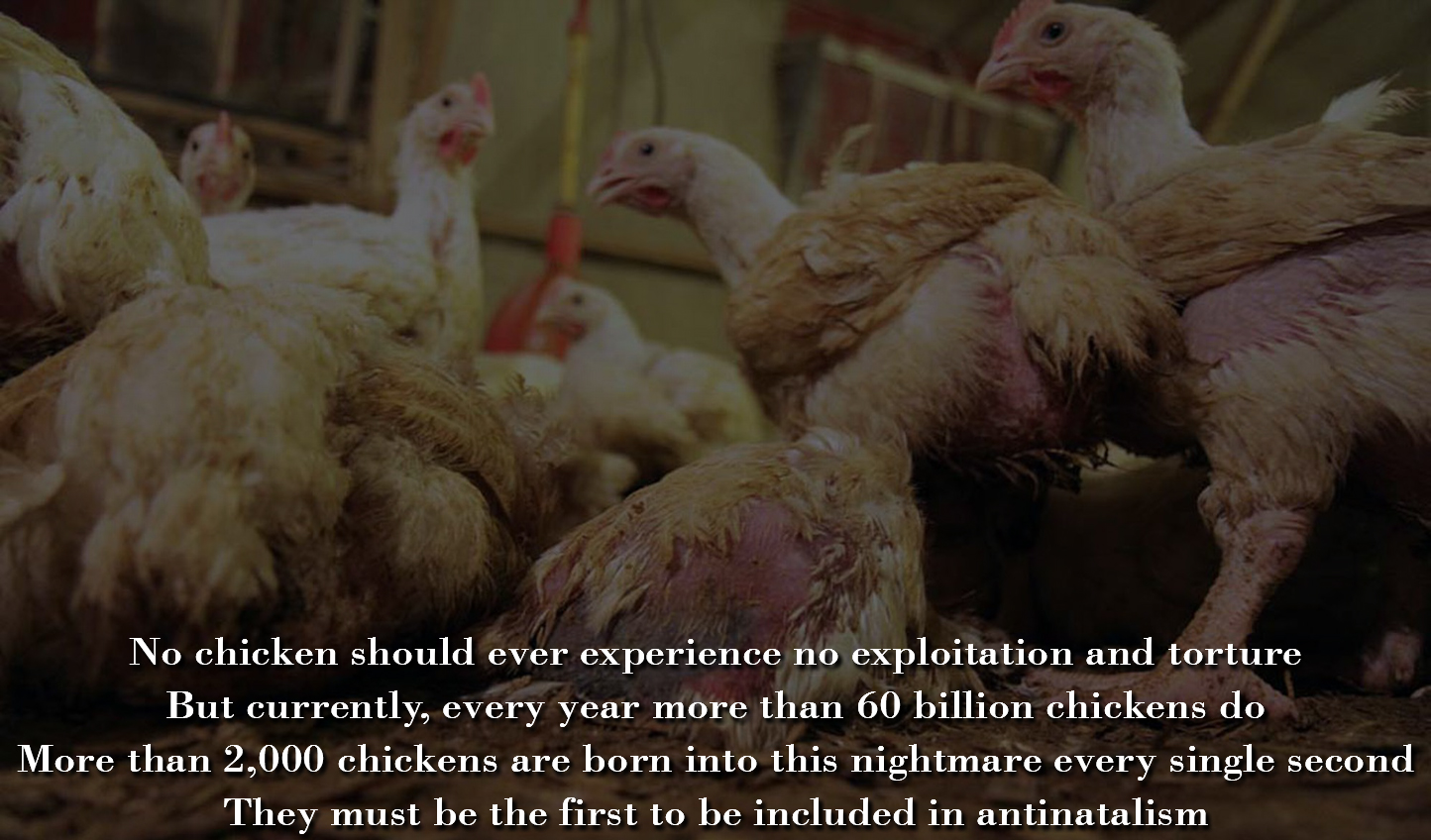

These animals must be the first to be included in antinatalism. It is beyond me how someone can be an antinatalist but actively contribute to the creation of the most miserable lives on earth.

Not suffering but manipulation is in the center of Cabrera’s antinatalism, but when it comes to animals exploited in the food industry both take place in the most extreme manner. In their case there is no need to argue where should antinatalism’s focus should be. Everything about their lives is extreme suffering and a product of total manipulation. There are no more accurate examples of the manipulation involved with creation than the creation of sentient creatures whose only function is to become someone else’s stake, coat, shoes, sweater, omelet producer, milkshake producer, bacon, or poulet. Every year more than 150 billion sentient animals are manipulatively created and manipulatively reared, explicitly, merely to be used as means to others’ ends. Is there a greater manipulation involved in creation than that?

And the manipulation goes further than the concept of creating billions of sentient creatures merely to be used as means to others’ ends, as every single part of their lives involves manipulation, even before they are born. Their genetics is manipulated so they would produce more meat, milk and eggs, their social structure is manipulated so to make the control over them more “efficient”, their confinement facilities are manipulated so to reduce costs to the minimum, the lighting in their confinement facilities is manipulated so they would think it is daylight even when it is not and so eat more and get fatter faster, their living spaces are manipulated so they would be unable to move and won’t “waste” energy on anything but growing as fast as possible, their food is manipulated in order to reach what is referred to by the industry as the optimal food efficiency, their water availability is manipulated so they would urinate less and so their bedding wouldn’t be replaced during their short miserable lives.

There is nothing more manipulative than the creation and the lives of animals in the food industry, so a philosopher such as Cabrera, who in the center of his ethics is manipulation, must be the last person who can justify participating in such a mass scale systematical manipulation.

And of all creatures, he chooses to consume the one that goes through the greatest manipulations of all.

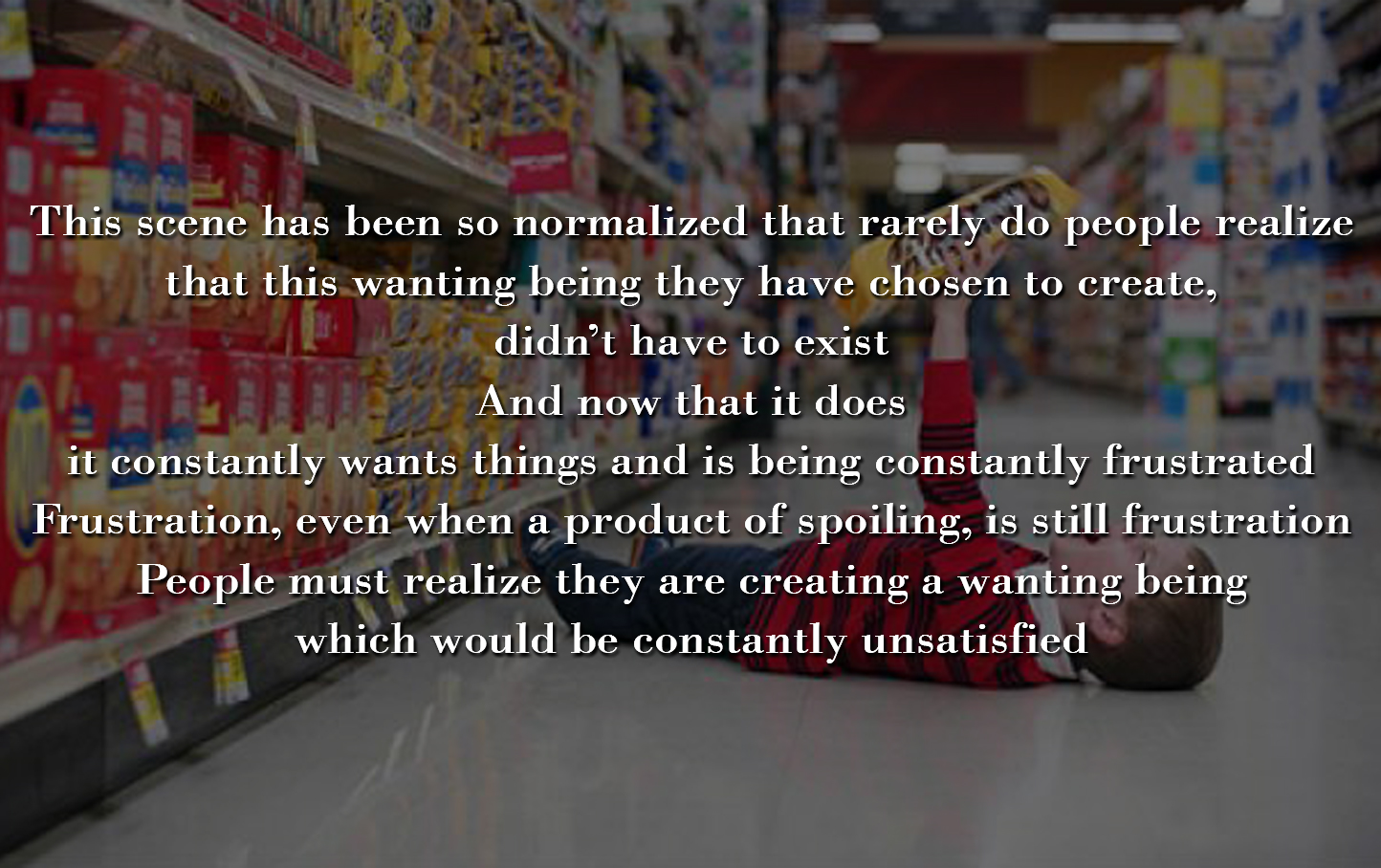

I would like to elaborate about the life of chickens in the meat industry because they are the strongest most evident example for why nonhuman animals must be included in antinatalism, especially when manipulation is in its center, as chickens exemplify more than any other creature the greatest and cruelest combination between suffering and manipulation.

The miserable life of every chicken in the meat industry starts when they hatch. Instead of being born to a defending, loving, and guiding mother, the first experience of every chick, is seeing thousands of other babies helplessly chirping to their absent mothers in the incubator they are born in.

Usually at the age of 2-3 days, all the newborn chicks are aggressively thrown into boxes and are shipped to the sheds where they would spend their entire miserable lives.

Despite that naturally chickens are social animals who spend most of their time foraging, they are forced to live their entire lives in crowded, dirty, soaked with ammonia warehouses, with no chance for any normal social structure, or any normal chicken behavior such as perching, foraging and dust bathing, no natural food, no sunshine, and no fresh air, which are all very essential for each chicken.

As the chickens grow, each one suffers not only from the diminishing space, but also from a series of severe health issues. That is mainly because chickens are being manipulated to grow about three times faster than normal, through a suited diet, special lighting plans, but mostly genetic modifications which aim to enlarge the more profitable body parts at the expense of the least profitable body parts of each bird. That causes each chicken to suffer from painful skeletal and metabolic diseases. At some point most of the chickens in each shed suffer from chronic pain and lameness.

The accelerated growth also prevents the chickens’ hearts and lungs from keeping up with the rest of the body, and so many suffer from related illnesses, among them are cardiac arrhythmia and heart attack. That is particularly amazing considering that chickens are slaughtered at the age of 7 weeks.

As the sheds get more crowded and filthier, the chickens who are forced to sit in wet, dirty, soaked with ammonia bedding, develop painful blisters, lesions and ulcerations on their already aching bodies. They often also develop painful eye infections as a result of the high ammonia concentration.

Their miserable lives are ended only by a miserable death. But before the chickens are slaughtered they suffer additional harms in the form of aggressive catching and loading onto the trucks, a horrible ride to the slaughterhouse in an extremely crowded truck, under every weather condition, no matter how freezing it is outside or alternatively how hot and dry it is, the chickens have no cover. Since it is unprofitable neither to feed the poor birds in their last day nor to give them any water, the chickens are starving and are dehydrated, a horrible condition which further contributes to the already extreme pain and stress.

The chickens are then aggressively pulled out of the cages in the trucks and aggressively shoved upside down into shackles on a conveyor belt. They are supposed to be stunned by electrified water, but many aren’t and so their throats are slashed while fully conscious. Some are even thrown into the boiling scalding tank, which looses their feathers before plucking, while still fully conscious, that means that they will be conscious when the plucking knives tear their bodies.

None of what is the written in the following paragraph is a recommendation, as no one needs to blow up the face of another animal to feed itself, but as an antinatalist, all the more so one that so highly emphasizes the manipulative aspect of creation, Cabrera could have at least argued that the only animal based product that he consumes is the meat of particularly large mammals who were hunted in the least harmful way. The rationale behind this is that particularly large mammals would provide him with meat for a long time and so the minimum number of animals would have to be sacrificed for his groundless speciesist and cruel insistence on consuming animals. The least harmful way is self-explanatory, and the hunting part is also highly related with the least harmful way as anything is better than factory farming, but it also relates to antinatalism as seemingly, hunting as opposed to the meat industry doesn’t necessarily mean that another animal would be produced. Practically it is very probable that another animal would because of how nature works (ecological niches tend to be populated according to available resources so when animals are murdered by humans other animals usually shortly occupy the area), but it is not as bound and structured as it is in the food industry. But more than the claimed above, the manipulation part is less present in hunting than it is in industrial exploitation of animals. So Cabrera of all people should have been highly opposed to the industrial manipulation and creation of other animals. But he considers nonhuman animals so little that he didn’t even bother thinking about options which would at least be less embarrassing than the bewildering self-contradiction that he made.

His response is insulting as it seems that he didn’t even bother respecting his questioners and listeners by giving a plausible answer. But of course the real problem, and the reason I mention this, is to exemplify how little importance and significance the suffering of trillions of animals matter to an ethical philosopher, and how deeply troubling must that be to all of us.

In the book A Critique of Affirmative Morality, Cabrera wrote a short Survival Handbook where he argues that since it is not optional to simply live and thereby affirmatively experiencing the world, one must conduct life which is ontologically minimal, radically responsible, sober, and completely aware that it is only a secondary morality, he calls it Negative Minimalism.

I fail to see Negative Minimalism in consuming animal products. It is the cruelest, least thoughtful, most wasteful and extremely environmentally unfriendly way one can feed itself. Supporting factory farms is Negative Maximalism. And when it is coming from someone like him, it is beyond inconsistency, it is criminal. This is not to be taken as a case of Ad Hominem. Cabrera is not another non-vegan antinatalist, he is the philosopher behind Negative Ethics. The case in point is that ironically he himself exemplifies an even stronger version of his own theory of how impossible it is for one to be ethical. His argument is that ethics is impossible even theoretically because not harming and not manipulating others is impossible even theoretically, but he gives us a personal example of how even in cases which it is theoretically possible not to harm and manipulate at least some others, practically people would choose to do so anyway.

The fact that people can’t avoid harming and manipulating others even if they wanted to, is a sufficient reason to stop the effort of trying to convince them to stop procreating and start the effort of making them stop procreating. The fact that they don’t even want to, makes that case indisputable.

Recent Comments