The following post is dedicated to a book called Debating Procreation. The book is divided into two parts. The first one is written by David Benatar, in which he presents 3 arguments for antinatalism. The second part is written by David Wasserman who criticizes Benatar’s arguments and presents a pronatalism argument.

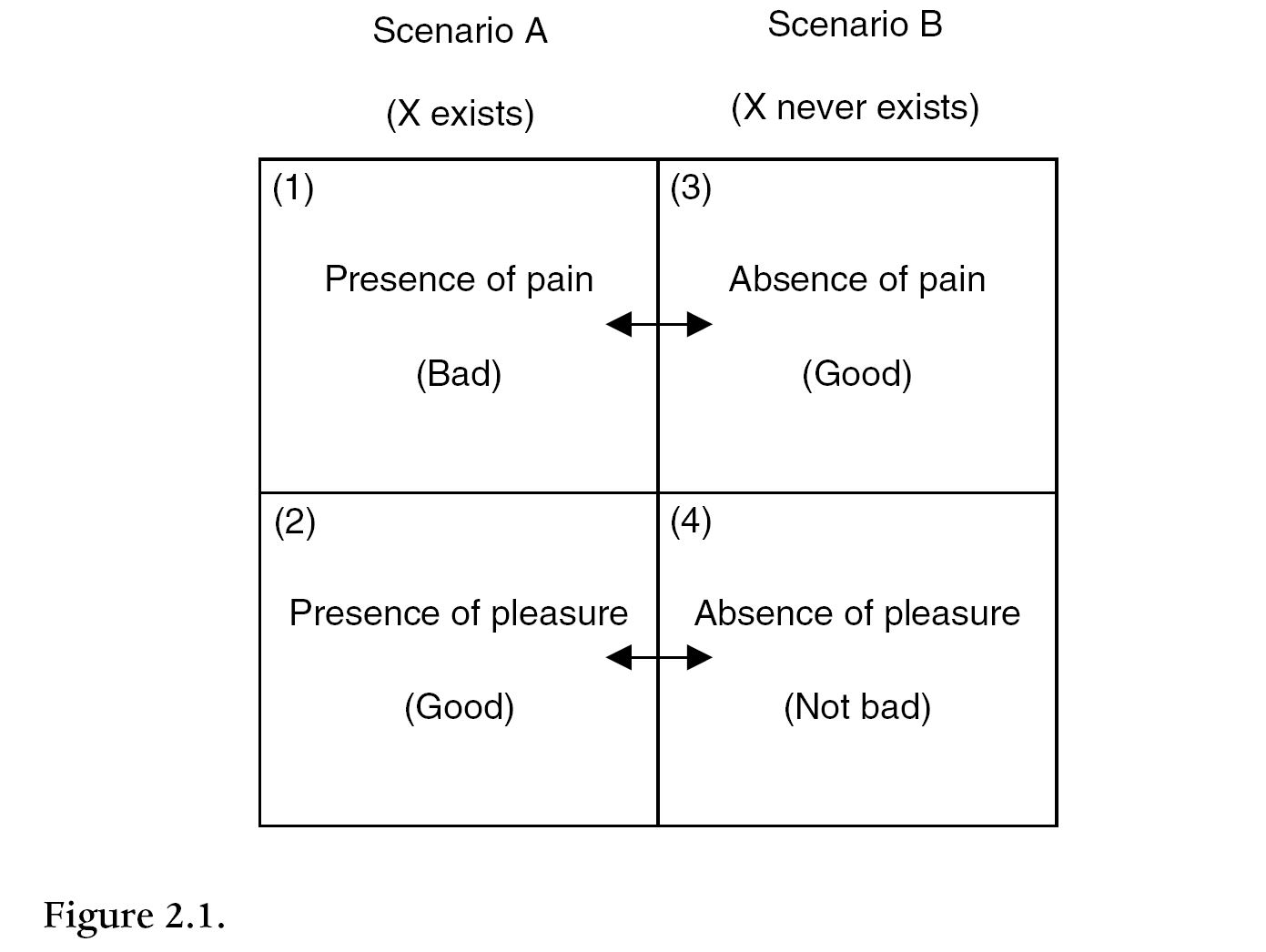

The name of the book is a bit misleading since it is not really a debate but rather two independent monologues. There is no Q&A section or even methodical replies by each side to the other’s arguments. However, Benatar’s half is highly recommended. Obviously it is hard to overcome the primacy of Better Never To Have Been, but in my view this text is much better and for several reasons: the problematic Asymmetry Argument gets less attention (but is still the first argument he displays), the Quality of Life Argument is presented here in an improved form (mostly since there is a greater emphasis on the risk aspect), and most importantly, after being totally absent in Benatar’s previous works, he finally included the harm to others as part of his antinatalism argument. The harm to others, in my view, is the most important antinatalism argument, so I was very pleased to see Benatar successfully and thoroughly construct it.

Unfortunately, he decided to title the harm to others argument as the misanthropic argument, and by that in a way, continue the anthropocentric tradition of focusing on the human race. Surely this part of the text is very unflattering for humanity, but it still focuses on humanity, instead of on its victims, who are supposed to be, at least in the harm to others argument, the center of attention. He calls the first two arguments of his part of the book the philanthropic arguments since they focus on humans as victims of procreation, and he calls the third one the misanthropic argument since it focuses on how destructive and harmful the human race is and so it better not exist. So all three arguments focus on humanity, while it could have easily been framed as antinatalist arguments for the sake of the one who does not yet exit, and antinatalist arguments for the ones who already exist and would be harmed by the ones who will be created, without even mentioning any biological species.

Yet, leaving the title issue aside, the misanthropic argument is in my opinion by far Benatar’s best argument.

Basically it goes as follows:

“The strongest misanthropic argument for anti-natalism is, I said, a moral one. It can be presented in various ways, but here is one:

- We have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing into existence new members of species that cause (and will likely continue to cause) vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death.

- Humans cause vast amounts of pain, suffering, and death.

- Therefore, we have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing new humans into existence.” (p.79)

Benatar devotes a considerable part of the misanthropic argument section to base the second premise of his argument. Based on some famous social psychology experiments, as well as other evidences from other fields, he details about humans’ violent tendencies, scary conformism and etc. This sub-section is called Human Nature—The Dark Side.

Then he mentions some notorious historical atrocities humans have inflicted on each other, writing: “Humans have killed many millions of other humans in war and in other mass atrocities, such as slavery, purges, and genocides.”

After specifying some of the violence humans inflict on other humans, he goes on specifying violence humans inflict on animals. In this sub-section he reviews the major animal exploitation industries, briefly describing the horrible life in each.

The last part of his foundation of the second premise is the harm that humans cause to other humans and to animals by the destructive effect they have on the environment.

He writes:

“For much of human history, the damage was local. Groups of humans fouled their immediate environment. In recent centuries the human impact has increased exponentially and the threat is now to the global environment. The increased threat is a product of two interacting factors—the exponential growth of the human population combined with significant increases in negative effects per capita. The latter is the result of industrialization and increased consumption.

The consequences include unprecedented levels of pollution. Filth is spewed in massive quantities into the air, the rivers, lakes, and seas, with obvious effects on those humans and animals who breath the air; live in or near the rivers, lakes and seas; or get their water from those sources.” (p.99)

Benatar is aware that most people would reply to his misanthropic argument saying that instead of preventing humans’ procreation we should reduce their destructiveness. But he disagrees:

“we cannot expect that human destructiveness will ever be reduced to such levels. Human nature is too frail and the circumstances that bring out the worst in humans are too pervasive and likely to remain so. Even where institutions can be built to curb the worst human excesses, these institutions are always vulnerable to moral entropy. It is naïve utopianism to think that a species as destructive as ours will cease, or all but cease, to be destructive.” (p.104)

And adds:

“Given the current size of the human population and the current levels of human consumption, each new human or cohort of humans adds incrementally to the amount of animal suffering and death and, via the environmental impact, to the amount of harm to humans (and animals).” (p.109)

And concludes:

Humans would never voluntarily cease to procreate, and would never cease to be destructive. That’s why we must aim at human extinction by forced sterilization.

Pro-Natalism

The second part of the book is written by David Wasserman who argues for the defense of procreation. He begins with a brief critique of Benatar’s asymmetry, mainly by mentioning the familiar aspects which were specified in the post dedicated to it, so there is no point repeating it here. He also criticizes Benatar’s quality-of-life argument, again mainly by mentioning the familiar aspects such as that Benatar offers unduly pessimistic assessments and inappropriately perfectionist standards.

A more interesting claim he makes is regarding the dynamics between Benatar’s asymmetry and his quality-of-life argument, a point which was mentioned in the post regarding extinction and pro-mortalism. Wasserman wonders why Benatar even needs the asymmetry argument (which he calls the comparative argument) and is not sufficed with the quality-of-life argument (which he calls the philanthropic argument), as Benatar:

“does not regard his comparative argument by itself as making the case that all procreation is wrongful. That case also requires his philanthropic argument, which is designed to show just how bad our lives really are. But if it is the magnitude of the harm that gives rise to a complaint, not the conclusion that life is always a harm, then it is not clear what role the comparative argument plays in reaching that conclusion. If careful scrutiny and critical assessment could show that life was very harmful overall for everyone, or almost everyone, then why would it matter for purposes of a moral complaint that it was also disadvantageous in comparison with nonexistence? The extremely high odds of a very bad existence would make procreation wrongful on any reasonable decision rule for risk or uncertainty.” (p.151)

So Wasserman thinks that Benatar should make do with his quality-of-life argument and doesn’t need the asymmetry, but he doesn’t agree with it for reasons which were mentioned above, and since he thinks that not only the risks must be considered but also their probability (which he claims are very low). To that he adds criticism of the attempt to use principles taken from Rawls’s Theory of Justice to constitute an antinatalist argument. Both arguments, the risk and Rawls’s Maximin, are worthy of a separate discussion. The one about risk can be found here, and the one about Rawls’s theory of justice can be found here. Therefore, I’ll not detail them here.

Intuitively, it would make sense to mainly focus here on Wasserman’s counter arguments to the misanthropic argument, given that this is Benatar’s novel argument in this book, and since I think that the harm to others is the most important antinatalist argument. However, Wasserman cowardly, poorly, and extremely speciesistly, evades the argument of the harm to others. His evasiveness is another proof that there is no way to seriously confront this claim. Wasserman’s response to the harm to others argument, as unbelievable as it is two decades into the third millennium, is almost Cartesian, meaning he simply denies the moral validity of animals’ suffering, this is what he wrote:

“I can only respond briefly, in part because I strongly disagree with Benatar’s weighing of the suffering of minimally-sentient animals, a disagreement we cannot resolve here.” (p.166)

Benatar details some of the common horrors done to animals on daily basis in factory farms, laboratories, the entertainment business, and the clothing industry, claiming that: “Humans inflict untold suffering and death on many billions of animals every year, and the overwhelming majority of humans are heavily complicit.” (p. 93) and Wasserman’s reply is that animals don’t really matter. That’s it. His “reply” is simply disgraceful.

Regarding the harms to other humans that Benatar details about as part of the misanthropic argument, Wasserman’s reply is that he disagrees most sharply with Benatar on the implications of human destructiveness and cruelty for individual procreative decisions. And surprisingly, the argument he uses to justify this claim, in my view, undermines moral philosophy:

“I do no think prospective parents must “universalize” about the likely consequences if everyone judged or acted as they do. I think the concerns about the consequences “if everyone did it” have far more relevance for policymakers than prospective parents. Although the latter must be cautious in their predictions about their children and may reasonably have concerns about the fairness and cumulative impact of similar decisions, I believe that they do not need to give this the same weight in their decisions as policymakers or other impartial third parties should in theirs.” (p.167)

Universalizing decisions and acting as policymakers is exactly how ethics should work. That doesn’t imply using Kant’s categorical imperative for any possible case, but Wasserman doesn’t even suggest exceptional cases or anything of this sort. He practically permits people to act as they wish as long as they are not official policymakers, as if only the actions of the latter have consequences. Obviously all actions have consequences, and all consequences must be considered ethically, especially when it comes to actions that everyone can do, like creating a new person.

What’s the point in morality if it is subjective? What exactly is the validation of ethics if every couple can be their own personal policymakers?

I wanted to seriously confront a serious opposition to the misanthropic argument, but Wasserman didn’t provide one. So I’ll focus in the rest of this text on three other points that he makes which I have found worth addressing.

The Good Of The Children

The first point is Wasserman’s claim, and the example allegedly proving that claim, that people can have a child for the child’s sake:

“Here is an example to give some flesh, and plausibility, to the idea that prospective parents can create children for reasons that concern the good of the children, or at least their shared good. Consider a couple who very much want children and decide to adopt. They are normally fertile, but are moved by the need to find homes for the many orphaned children in their country now housed in institutions. This, however, is not their primary reason for adopting; it merely tips the balance. Their reasons include wanting the fulfillment of raising a child from a young age, seeking the uniquely intimate relationship that a child develops with its parents, and giving the child a good home—among the reasons given in surveys of prospective parents. They regard these as reasons that could be served equally well by adoption or conception. Just as they are going to start visiting orphanages, their government prohibits adoption—orphans and abandoned children will be wards of the state, with temporary foster parents in special cases. The couple is very disappointed but quickly decides to go with “Plan B”—they conceive a child for the same reasons.

The point of this example is not just to illustrate that adoption and procreation may be done for similar reasons. As important for my purposes, it suggests the limited role that the actual vs. contingent existence of the child may play in the sorts of reasons prospective parents have. The couple in my example starts by seeking to find a child of their own who already exists, or whose existence is not contingent on their actions. Barred from doing so, they shift to creating a child. But their reasons for doing the latter are largely the same as their reasons for having sought the former. The desire to help existing needy children was just a tiebreaker.” (p.190)

I fail to see the reasoning behind this argument or the explanatory power of this example.

If anything this example proves the opposite. It goes to show that these people want a child of their own, not to help someone in need. If they find no difference in that sense between adopting a child and creating one, then clearly the interests of the child weren’t their motive, as in one option there is an existing child who is orphan and so in need, and in the other option there is no one who needs anything.

It is the parents who wanted the fulfillment of raising a child from a young age. Before they have procreated, that child didn’t exist and so didn’t share their want. It wasn’t in the interests of that child to be raised from a young age. Non-existing persons don’t have interests and no wants, so it can’t be for the good of the child. An existing child on the other hand, does have an interest to be raised from a young age. That’s a very important difference between the two cases.

And same goes for the second reason – no non-existing person is seeking the uniquely intimate relationship that a child develops with its parents. But existing persons – prospective parents, and even more so orphans – probably do. In the case of procreation, seeking the uniquely intimate relationship is the parents’ want imposed on the child they have created.

The last reason is no different. While orphans desperately need a good home, because they already exist but don’t have one, non-existing persons don’t need a home, or anything else for that matter. The need for a good home was created correspondingly with their creation.

There are many ways to really act for reasons that concern the good of the children, but none of them includes creating ones. There are many children who have parents but don’t have other things that would make their lives better, why not focus on them? Why not help children with their homework? Why not volunteer to babysit them every once in a while? Why not starting a children class for free? Why not choose professions that focus on care for the good of the children like being teachers, doctors, social workers, kindergartners, Clown Cares, and etc.?

If it was really benefiting children that was on their mind they would invest most of their time, energy and resources on existing children who are in need, instead of on someone who they have created its need by procreation. It doesn’t make any sense. Anyone who wants to provide a good home for someone in need, who feel they have so much love to give, who want to do good for others, can adopt a homeless dog from a shelter.

Wasserman argues that “For both adoptive and biological parents, the child’s “bare existence” is a necessary condition for fulfilling their primary end but is not, or need not be, a primary end in itself.” (p. 193) But that doesn’t explain choosing the most senseless option. And even if there wasn’t any other option for giving and the only option was truly to create a need, it is still treating someone as a means to an end. The child had neither interest nor any say in being created into existence. The child is a mean to the parents’ ends.

Unfortunately there is no shortage in philanthropist aims in this world, why choose to create a new one and focus on it? With so much misery in the world why create a new need? Doesn’t it make much more sense to focus on an existing need?

If this world lacks love and meaning, what is the point of increasing the number of creatures who need love and meaning? This is the stupidest form of giving.

Or, of course, that it is not really the reason why people procreate. The real reasons are that people feel powerful when someone is totally depended on them, they feel needed and important, it fills the empty and pointless lives of people with meaning, they believe it would save their relationships, it eases loneliness, it soothes their fear of getting old with no one to take care of them, biological impulse, genetical vanity, immortality illusion, continuity illusion, it makes them feel normal, it makes them look normal to others, conformism, stupidity, accident.

Tantrum in the Mall as a Sip of Lifelong Frustration

The second point I want to address is Wasserman’s argument regrading parents’ duty towards their children: “Even the most spoiled child should recognize that his parents do not have a duty to maximally satisfy his interests; that their own interests, as well as those of a myriad of others, appropriately limit their duty to satisfy his.” (p.154)

This claim might be true when that child would grow up but in real time that child suffers. As an adult that child might regret being so spoiled, but that doesn’t serve as compensation for the frustration at not getting maximum satisfaction. The fact that the child is wrong doesn’t make that child less wanting and less frustrated. Many children tend to keep crying and screaming when they don’t get what they want even after they are explained that what they want is exaggerated or that there is no option to provide them everything they want, any time they want it. And that, in my view, holds much more than might seem. Only because it is obvious that children don’t get everything they want, and also because the crying and screaming scene is so common, people don’t stop and think about the fact that they are creating someone who would want everything possible, and would have to compromise on very little of that. They don’t stop and think about the fact that they are creating someone who would be constantly frustrated.

And it doesn’t end at childhood, it continues throughout their whole life. It is only refined along the years, when children learn to suppress some of their desires (which might come out in different ways that are not necessarily more positive), or control their urges and desires (which again, doesn’t always turn out to be better), but this is forever. Frustration is forever.

The crying and screaming scene on the shopping mall floor because the child got a little bit smaller toy than wanted, which have become so familiar that it turned into a parenthood cliché, is much deeper than children being extremely spoiled. There are so many advices for how to deal with these scenes. Most blame the parents. And they are right, but not because they don’t know how to set boundaries for their children, but because they don’t know how to set boundaries for themselves. It is the parents who are too spoiled and selfish and careless about the effects on others. It is them who acted to promote their own interests and so created a toy for themselves. They don’t know how to postpone gratifications and therefore have created a new small unit of exploitation and pollution which doesn’t know how to postpone gratifications.

This scene, which is considered as parents’ initiation, and which some go through several times during a lifetime, has been so normalized, that rarely do people realize that this wanting being they have chosen to create, didn’t have to exist, and now that it does, it constantly wants things and is being constantly limited. Frustration, even when is the product of being spoiled, is still frustration. People must realize they are creating a wanting being which would be constantly unsatisfied. Quieter children who don’t cry and scream when not getting something, are viewed as more mature and better educated children, and less spoiled. That might be true, and they might internalize that being spoiled is not good, but looking at the screaming children getting their toys, makes them frustrated. Some of them want that toy just as much, but they have internalized the expectation of them to suppress their wants.

You can look at the mall scene as merely children being too spoiled, or as lack of parental authority, or the consequences of the snowflake attitude, or the effects of the consumerist society, or a little bit of each. But it is also a window of opportunity to comprehend that creating a child is creating a bottomless pit of wants which can’t be satisfied. Of course this example is totally marginal but it is not trivial just because it is so common. It is a window of opportunity because when children are in a state of tantrum there are almost no emotional impediments. Obviously, these scenes are in many cases very manipulative (children are not yet equipped with many tools to help them get what they want so they use what they have which is crying and screaming and kicking as hard as possible), however, they nevertheless express true helplessness. These incidents often occur when children feel they have no control over the circumstances. They want things but are helpless in getting them. Helplessness can often produce fear as the children are depended on other people’s wishes. These scenes are also much more raw than the customary desires of adults, as they are highly socialized to navigate their desires in more subtle ways.

In light of the horrors Benatar specified in the first part, obviously the mall scene doesn’t only pale but seems absolutely ridiculous. But I am not bringing it up as an example of human frustration, but as an example of the greatest trivialization of human’s most trivial frustration. What makes it interesting is the glimpse it offers for everybody to publicly see how much of a lump of wants a person is, and how much frustration even the most trivial scene contains, and how trivial frustration is in people’s lives. The scene is so trivial that everybody accepts it. The child would learn that we don’t get everything we want in life. Unfortunately the adults don’t learn that they shouldn’t create frustration, even if it is very very marginal.

Parents are forcing their children to give up the toy they want, because they have refused to give up the toys they wanted to create.

Russian Roulette

As mentioned earlier, I have addressed the risk argument in a separate text, so here I’ll make do with a quick note on Wasserman’s remark regarding Benatar’s risk imposition metaphor which according to him:

“gains spurious strength, I suspect, from the Russian roulette simile he employs, which has prospective parents pointing a gun at the head of their future child; a gun with a high proportion of chambers loaded. This simile is misleading. As the literature on the ethics of risk imposition and distribution points out, it matters a great deal if the threatened harm will be imposed intentionally. Shooting someone with a loaded gun is intentionally harming him, even if the discharge of a bullet had been far from certain.” (p.165)

One might argue that the parents are not always the ones who pull the trigger. However, they are definitely the ones who set the target, and they are the ones who load at least some of the bullets.

Parents who know that their children would experience suffering, and every parent knows that suffering is inevitable at least at some point in life, are setting the target. Had that child not been created by them, there would have been no one to shoot at.

They are loading some of the bullets by passing physical and mental traits which their children would suffer from. Other starting points might also affect the life of that child. If the environmental conditions are bad, then the gun is loaded with even more bullets. And if it is quite certain that the child is prone to a serious disease, or that the parents are prone to a serious disease, or have a violent history, for example, then the parents are also pulling the trigger, at least in some rounds, and the other rounds are being completed by other factors.

Since parents are creating persons out of their own will and for their own benefit, they are imposing an intended risk on someone else’s life. They don’t intend to harm their own children, but they intendedly ignore the fact that their children would surely be harmed.

When considering the harm to others, since the parents are the ones who provide their children food, clothes, energy and every other harmful aspect involved with supporting their life, they are definitely held responsible in every possible way. They have created this consuming being which wasn’t there and wasn’t deprived of anything before they have decided to create it, and now it exists, and it is hurting many sentient creatures in many different ways for no justified reason at all.

Considering the enormous harm every person inflicts on others, and the loaded weapon is not a gun, but an aircraft carrier.

References

Benatar David and Wasserman David, Debating Procreation: Is It Wrong to Reproduce?

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

Benatar, D. Better Never to Have Been (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006)

Recent Comments